Nowruz

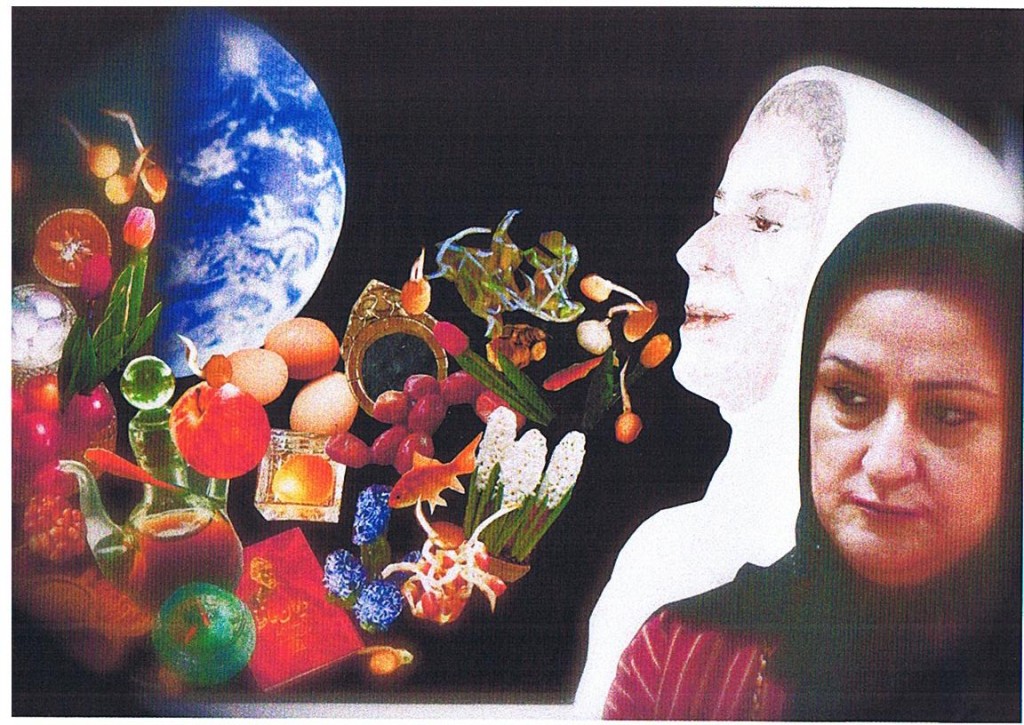

Val Bonney

Response

PERSIAN NEW YEAR

by

Lisa Leibow

Inspiration piece

Spring was coming the next morning at seven o’clock. Sanaz felt so ready for it. More than ever, she was anxious for everything to bloom, and for the newness. Her children were grown and on their own. She was free now.

In her family they celebrated big. It was their New Year, the Persian New Year. It was the beginning. Sanaz had turned 62 last month. And in 62 years she never failed to celebrate the New Year.

Sanaz observed this holiday even as a new immigrant to America. That wasn’t easy, because there were so few around with whom to share the festivity. When she first moved to the United States, there were no other Iranians.

Think about Christmas, Rosh Hashanah, or even the Western New Year—January 1. What if you went somewhere and nobody knew about it? What if nobody ever even heard about it? Not even any mention of it. It was a celebration. It meant fun. So, what was she to do? Nobody even talked about it. Even though she had no one to share it with, as was customary, each year she cleaned the house. She aired the house by opening windows and doors. She washed and bought new clothes. For the year to start, one must have been well-fed, obtained brand-new clothes, been happy, and had everything very clean. That was the way to have a proper New Year celebration.

Once in America for a while, Sanaz learned that Americans, too, adhered to the custom of spring cleaning. She observed that Christians had Easter, which incorporated a rejoicing of springtime, and that Jews had Passover, which was a holiday of springtime too. She thought the customs likely came from the same origins; every religion had these traditions. People long ago all had this way of life. And then when religions developed, they adapted the traditions as their own.

But the coming of spring had been a tradition of Iranian people for 3000 or 4000 years. Even after Islam came, the leaders of that religion tried to change the traditions and make them totally Islamic. However, Islamic leaders could never stop the people from continuing these ancient rituals.

Even in the absence of any community to share, Sanaz rejoiced each spring equinox for her children. She wanted to make sure they remembered who they were.

She prepared special food for the New Year. She set a ceremonial table called the cloth of seven dishes, all beginning with the Persian letter cihn, which makes the same sound as the letter s. On the table, she set these symbolic dishes: Sabzeh, or sprouts, usually wheat or lentil, which represented rebirth; Samanu, a pudding in which common wheat sprouts were transformed and given new life as a sweet, creamy pudding; Seeb means apple and represented health and beauty; Senjed, the sweet, dry fruit of the Lotus tree, represented love; Seer, which is garlic in Persian, represented medicine; Somaq, or sumac berries, represented the color of sunrise, with the appearance of the sun Good conquers Evil; and Serkeh, or vinegar, represented age and patience.

Sanaz’s favorite part of the preparations was to put seeds in water to make them sprout. Once sprouted, she took them out and put them on the plate with the other food. She usually liked to sprout lentils instead of some other bean, because lentils grew curly. The curly sprouts looked festive when she topped wheat pudding with them. The whole celebration was a combination or mixture of celebration of spring and the New Year.

To her it made sense to celebrate the New Year with the coming of spring. It was the time when nature was regenerating after winter’s hibernation and dormancy. To her it was supposed to be New Year.

Sanaz did all these things with her children, to make them know their history: she kept them out of school for that first day of spring, planted seeds with them, took them shopping and bought new clothes for them, and showed them the seven “s” things. Every year the holiday was at a different time. Sometimes it was at five o’clock in the morning. Sometimes it was at five in the afternoon. Sanaz would wake the children at the start of the New Year, even at two in the morning—“Happy New Year, darlings! Come on, it’s the New Year!”—then, she was the only one to get the word of the New Year in the air. There was nothing in the air from anyone else in the community.

Her husband often got angry and said, “Sanaz, why are you doing all of this? We live here now. You should either celebrate Christmas or our New Year, not both!” He would make such a big deal.

Sometimes she told him, “If you make a big deal, I will celebrate Chinese New Year, Indian New Year, African New Year, our New Year, Western New Year!”

They had so many arguments about it.

But this year was the first year in her whole life that Sanaz did nothing. She did not put her seed in water. She did not prepare the cloth of seven dishes. Now, it was too late.

Years ago the only way she knew that the New Year was done was to look at the time. These days, in America, there were Iranian television stations and big communities of Iranian Americans who were celebrating this, so it was really in the air: the beauty shop in Sanaz’s neighborhood was very busy. All the women came and got manicures, pedicures, facials, and waxing all over. They bought new clothes. They got ready for the New Year. So you see, she didn’t know why she was not ready.

Every morning she’d say, “I need to put the seed in water.” Then she didn’t do it.

Sanaz didn’t know why she failed to do it. It was a symbol of renewal to make her strong. Maybe there was no New Year for her this time. Maybe she should’ve bought a new dress to get out her feeling. People said, “Just buy the seeds already sprouted.” Sanaz couldn’t do that. That was not the reason for it—not just to have the small plants. One must actually put the seed in the water.

Her children were grown and on their own. She was proud of her years of single-handedly holding on to these traditions. She came to a new world and passed the torch to a new generation. She was free—free of stories, of bondage, of struggling to make it happen. She grasped that, all along, the newness had been in her every breath, in her realization of every moment. No country, no religion, and no tradition made her who she was or found her what she sought. She didn’t need to put the seeds in water to symbolize strong roots. Sanaz found the seed of her essence so strongly rooted in her heart that there was no need for the ritual. She didn’t need to put any seed in water; her whole life was a celebration of newness and magic.

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.

One Comment

Once again, I have enjoyed and benefited from the SPARK experience. Lisa’s prose sent me Googling after the Persian New Year and I learned so much. Creating the response had me thinking deeply about how our cultural, emotional and religious fervour mellows with age and how our view on what is important can change.

Thanks, Lisa – and thanks to Amy for running this fabulous project!