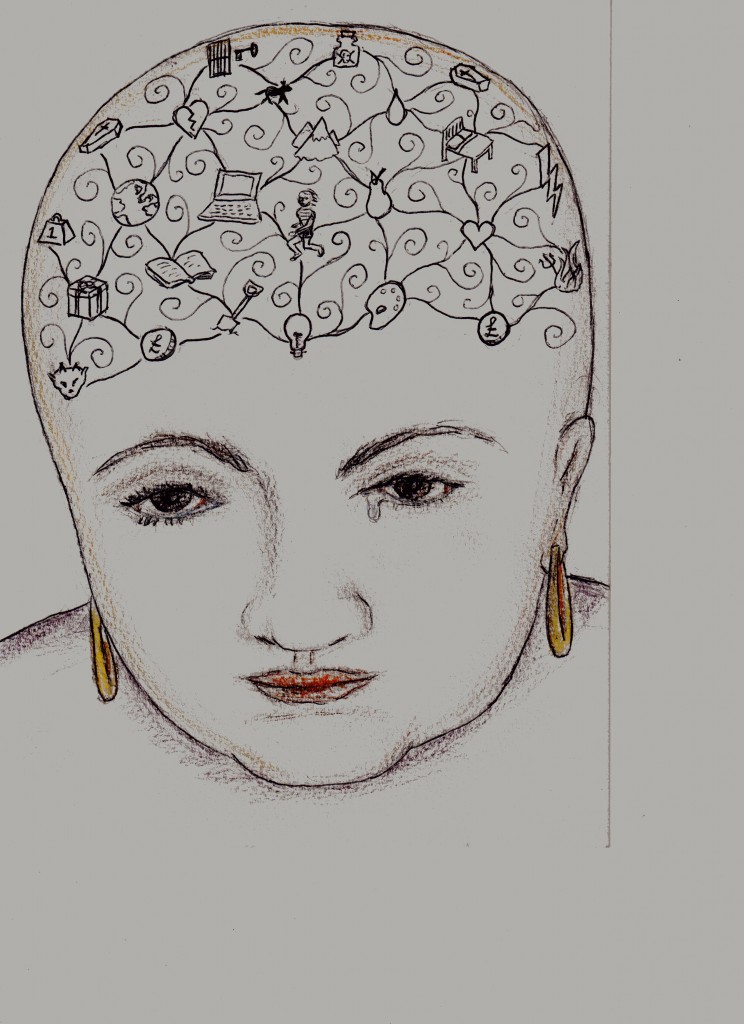

Val Bonney, “Neural Pathways.”

Inspiration Piece

Maureen O’Donnell, “The List.“

Response

Even in her twenties she used to stand in front of the mirror and pluck out grey hairs. She must have thought he wasn’t looking, but every so often he saw her do it as he walked down the hall, past the open bathroom door.

-Hair dye is for old women. Or for people insecure about their age, she’d say.

Still she would stop in front of that mirror, tease apart the dark strands, and then jerk the defector free.

Funny how that’s what he thinks about now, with her leaned against him, their bodies bridging the cheap plastic armrest that angled awkwardly between them. He shifts just enough to kiss the top of her head, lips to knit cap. She stirs, eyes closed, and he listens for the sound of wheels on cold linoleum.

He remembers how it started, how they never saw it coming.

-I’m tired, she said then, once in a while, and then more often.

-Sleep. I’ll come back for you before dinner.

And when he returned, she had dressed and her eyes were bright. Until the next time the light went out of her and she huddled beneath the covers.

-I just can’t shake this cold. Can you pick up more lozenges?

-On the way home from work, sure, he had said.

-And maybe some tea?

-I hope this isn’t catching. He had meant it as a joke.

Eventually she went to the doctor, who sucker-punched them with a long speech about small bees and lymphoma cells. Too many things he didn’t want to know.

The chemotherapy had failed, and he finally had to learn.

He hears a rattle down the hall. It is one of many sounds: beep, whir, the ring of a phone, a woman’s soft voice across the desk. He feels the intent of the rattle, knows that it’s a transport bed coming for them. For a moment he feels hunted and his arm tightens around her. She stirs and mumbles.

-Are you sure you’re ready for this, he asks.

As if it isn’t too late to go back. As if they hadn’t committed to the injections, signed the dotted line, screamed a few times at the insurance company over the phone, counted down the doctors’ visits and blood cell readings until the time was just right.

-Yeah, she says.

He helps her into the gurney, kisses her, and then she is gone. It’s only then that he remembers the list in his pocket. On it are things he wants to say before they wheel her away, put her under. He gets up and tries to follow, but meets a wall of gentle, compassionate resistance.

-Sir, I’m sorry, but you’ll have to wait, says the doctor, straightening his stethescope.

-Mr. Boone, we’ll call you when she’s up.

-I’m sorry, Mr. Boone, it’s a sterile room. You can’t go in there.

All he can think about is the things he forgot to say. He will never forgive himself if he loses her without saying them.

#

They release her twenty-six days later, to a fresh-scrubbed house and a husband who is terrified of any sneeze, dust spec, mold spore, or chill wind that might push her over the brink. For another three weeks he tries to get her to eat, feeds her like a baby, cleans up the food that doesn’t stay down.

He talks to her, talks of the things she loves and the things they still must to do together. Sometimes he thinks she listens but most times he knows she is sleeping or staring or too sick to understand. When she has the energy, she cries and yells and vomits the pills and accuses him of poisoning her. When she doesn’t, she turns to face the wall. He talks to her anyway.

He ignores telephone calls and the stockpiles of tasteless casseroles that threaten to spill out of the freezer. He listens with quiet anger to the people who talk about her as if she is already gone, thanks them for coming and does not let them in again.

On the day, as he changes the sheets, she tells him to feed the Nora’s Tuna Noodle Surprise to the squirrels. He smiles for the first time in months.

#

She leans against him, light as a feather and warm, wrapped in a blue housecoat. Her hair is growing back now, fine down, and pale. White.

-I must have slept through most of it, she says.

He knows that she did not and keeps his silence.

-I remember dreams.

-What did you dream about? he asks

-So many things. You were in some of them. And some were awful. I dreamed about wanting to die. Isn’t that a terrible to say, after everything?

-What was I doing? In the dream, I mean.

-Talking to me. You said beautiful things. They made me cry, I was so happy.

He opens his mouth to tell her that it was him, that none of it was a dream. And then he stops himself. He glances at his wife, at the thin hair soft and pale as down that’s finally growing, wisps, from her scalp. The strands are not enough to cover her scalp, and so he can see that too: the dark suggestion of blood vessels beneath her scalp, like a child’s scrawl or a surgeon’s pen on her skull.

He stares down at her, stares past hair and scalp, through her skull to what they both hope is a brain not seeded with those cancerous, aggressive cells.

-Do you want me to say them now? He asks.

-Sure. She nods.

He talks, about the day they met and the day he decided to ask her to marry him, which was actually two months before the day they got engaged because it took him that long to work up the nerve. He talks about the things she loves: her art, her books, the furniture they picked out together, and the last time they went camping when a thunderstorm nearly collapsed their tent. He talks about their friends and her visitors, about the spot beneath her ear that he loves to kiss and the vacation he wants to take with her.

She says nothing, and it takes him a while to realize she has fallen asleep.

He shifts, just enough to kiss the top of her head. His arm tightens, just slightly, around her. The contented sound she makes is all that needs to be said.

—————————————————— Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs

to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything

you see here without express and written permission from the

author or artist is strictly prohibited.