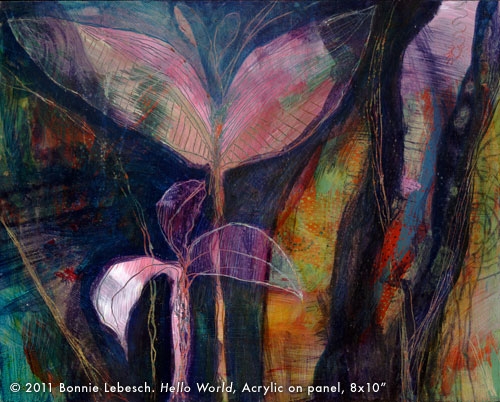

Bonnie Lebesch

Transparent

I was married once, to Maxine, she died of cancer seven years ago, after just five years of marriage. After enduring the empty days following as best I could, I found a dog that seemed happy to see me. I called her Max, which gave me a good excuse to keep talking to my wife. She’s furry and has a wet nose and climbs onto the bed every night and does her best to take over before dawn. She’s a lovely mutt, basset hound ears on a retriever body. Max’s favorite spot is a dog bed by the couch in the living room where we sat and watched TV. She loves honey mustard on her dry food. She’s a little overfed and I have a bad habit of feeding her from the table. Around the time I first saw the plant, Max stopped eating much of her dinner.

I’m a botanist, and in my fifties and all the literature says my most creative years are in my wake. The younger minds at the lab seem to be making all the breakthroughs. The people I work with are researchers, witch doctors, bureaucrats, all of us on a long term federal grant to find novel solutions to implacable ailments. We specifically seek cures in things of the earth and our field people spend a lot of time in jungles and other wild areas, sending back curiosities. We’ve had bugs, lizards, and other creepy things that were new to us, but mostly we get plants. A few show promise but of those most don’t show us any miracle. Of the plants, the ones that don’t work but that I find intriguing I bring home. Most die, because my Minnesota home is so far from the tropics, where virtually all of our subjects are found. The plants I don’t take a shine to are destroyed, fed to an incinerator, for the plants we work on are sometimes dangerous in themselves.

The plant? I nicknamed it ‘Transparentus Amazonus’ and I know it’s silly. It was discovered, like so many of our subjects, in a dank Amazonian rain forest. It was run through the usual battery of tests by the bright young minds but failed to impress them. It was on a shelf to be destroyed when I first saw it. I took it home, curious to determine why its leaves were transparent.

I never did unlock the transparency clue but learned Transparentus was a magnificent organism. The leaves are transparent when they bloom, and remain that way until the plant matures, a three month wait, and then the leaves take on the look of tanned leather. The leaves secrete a sap that tastes awful – don’t ask – and the sap dries up at maturity. The bright young minds tested the sap but – as I said – – it failed to interest them. If I were to spend the rest of my life on this plant, and I could, I’m sure I’d find the transparency was a defense mechanism; that’s how these things usually play out.

I sat the plant on a window ledge in my bathroom, the dampest spot in the house, most similar to its Amazonian roots. At night, with my neighbor’s back porch light on, the beams hitting the plant cast light in a faint, milky shadow. It had a sickly sweet reek, a hint of organic rot, so it wasn’t going to make it as an air freshener. But it was amazing to look at and I didn’t mind its stink.

Max sniffed it the first day, as she did all the plants I brought home, then turned away, not unusual. She wouldn’t come into the bathroom when I called her, because the plant was there. At first I suspected the smell drove her off until I thought of what dogs like to roll in.

Did I mention its growth rate? I had to repot it four times in four weeks. No wonder the Amazon is full of plant life.

How did I discover its curative powers? I’m sure you’ve guessed, it was Max. She was eating less and less, left more of her food to dry up in the dish. From being portly, one evening I picked her up and felt her ribs for the first time. Then it became plain to see that she was starving, and I guess I’d been denying there was a problem. I got on the phone and I took her to the vet. I held her protectively on the examining table, feeling her heart thump – Max definitely had lab coat syndrome. The vet gingerly got her mouth open, then shone her light in. “Hmmm…” she mumbled thoughtfully. “I’d like to give her an X-ray.”

What do you say? “Sure.” That initiated a two hour wait, and after walking Max around a small park like setting turned into a minefield of dog turds, I was paged to the examining room. The vet showed me x-rays that could have been images from a T-Rex. “There’s a tumor.” She touched a spot. “In her stomach. I could operate,” she began, “but we don’t know if she’ll even wake up from anesthesia.” There was concern in her voice, if not trepidation – would it just be hard on Max or did she doubt her own surgical skill, I didn’t ask.

Max was exhausted so I took her home. “Max, I didn’t know. And I’m not sure what to do. Maybe I can call another vet, get another opinion.” I cried much of the way, Max licking my hand.

The next morning the plant had tipped over on the shelf from its own weight and I had to set it on the floor.

I watched Max that week more closely, looking for signs of weakness, signs of deterioration. When the day came that she couldn’t climb the steps to the bedroom, that she couldn’t at least drink milk – her favorite – that point where her life was too miserable to continue, I would have to put her down.

On the fourth day, Max jumped up the steps two-at-a-time, energy she hadn’t had for years. She wolfed down a full plate of food and showed no sign of losing it; she ate everything put before her and I had to tap her nose when she made a play for some cake I’d set on the coffee table. On the sixth day I weighed her inexpertly and she’d gained three pounds. And there was no ignoring the smile of a healthy, happy animal.

That was Saturday. I watched her Sunday, wondering how she’d turned the corner, and twice I saw her approach Transparentus and lick its sappy leaves. Each time Max licked it, she licked it clean, but came back for more. She licked the leaves at least four times that day, I know, I set up a video monitor.

I remember thinking, perhaps my best work is not behind me. This was as valid a path of discovery as exists. I had found a cure for stomach cancer, in dogs. Besides my personal joy at Max’s health, I started getting ambitious.

I tried an experiment of my own: I took a leaf and crushed it and collected roughly twice the sap I guessed Max had licked. I estimated how much sap represented four doses a day, and sprinkled it on her dinner. I didn’t have toxicity data, though I knew she could handle small doses. I just prayed more of it would be even better. Scientists do more praying than you’d be comfortable seeing.

She seemed to grow younger; she had more energy and barked and chased squirrels. How long had she been sick, I couldn’t help wondering. A few days later I took her back for a checkup and the vet was amazed to find the tumor in complete remission. “I’ve seen tumors go away, but never this fast. We got lucky this time,” she said, beaming.

Last Tuesday I set the pot on the garage floor — did I mention that it grows fast and takes up more and more space — to water it, when the phone rang. When I returned, Max had chewed down every bit of Transparentus, to a woody stem that dried up and died.

I had sent off a sample to a friend who has recently contacted me; Transparentus Amazonus is what gardeners call an ‘annual’. It blooms just once, from a bulb. We’ve been told by the scientific community that a cure for cancer is out there somewhere. Like a train barreling past, I just saw it and wonder where it will stop next.

2 Comments

Bob this is a great story! Love it, especially because I have a deep appreciation for healing plants. I’ve worked a lot with chinese herbs in my artwork. So glad you picked that out. -Bonnie

I am a survivor of two cancers. Wonders never cease!