The Ocean Becomes The Drop

By Annie Perconti

Response

Ocean Boy

Susan Gordon

Inspiration piece

I was born of the ocean. I was born of the sea. I clung to a soft and moving cliff as the waters surged all around me. There was a time when I fell and drowned, so I am unafraid of drowning. I woke again, with my great lidless eyes taking in the slap of waves around me, above and below. I didn’t have hair; I didn’t have lungs; I was tethered and floating. It was a peaceful place unless the woman, who carried the sea within her, my mother, was sad, then all of me sloshed, discontented, longing to soothe the one who usually soothed me. But mostly there was joy. If she was laughing with the man she called Charlie, or was happy pushing Ruthie on a swing, I danced in the ocean, bumping joyful, kicking my sea legs, taking strokes with my arms with the hands with their new fingers, wishing my salt water roundness was bigger.

And then one day it was and it wasn’t. I was pushed, pushed on a tidal, moon controlled surge, head forced down, down against a circle of bones, bones that would not give way. I was drowning again, movement taken from me. My will, my freedom disappeared and I couldn’t tell if this forcing of me was her will either. She moaned, panted but seemed to be riding each wave until some poison flowed into the ocean. She was silent and I was ill, still pushed by some force into the hole, against bones that softened and gave way and I was born into light and cold air. I took my first breath, screaming for the warmth of tight water.

But I remembered, she remembered when I had ridden the waves inside her. A late January baby, she had me back in swimming water by June. She held my body in a pool in the Catskills; she held me strongly in one soon to be shaking arm and with her free hand she lapped small waves of water against my warm body. When I was six months old, when I was one and a half, when I was two and half, it was my mother, who, first cradled me, and then supported my first steps in belly deep, chest deep water. She would gently roll tiny waves against me; she would cup her hand, and dribble a warm, wet baptism over my curly hair.

I remember the day my Mommy and Daddy took me out to Far Rockaway, the beaches that were at the end of the subway line, the beaches where Queens ended and its’ streets with white wooden shotgun cottages, built cheek to jowl, met deep and moving water. I remember the great rolling ocean, its’ pounding roar that shook my two year old legs; I could feel the sand tremble and slide back into the water on the wave that broke, lacy white, but pulling, pulling sand, shells, sea weed it had cast up back to its’ breast.

I stood there and then I pulled my Daddy, stronger than Mommy, into the first waves that I claimed: mine, mine. Mommy stood crying as I raced into the ocean that was her, me and something wild and boundless. Daddy said, “Jump” and I jumped; Daddy said, “Hold your breath and dive” and I did. He had his arm around my belly but already I was seeking to be free as we rose behind one crashing wave and in front of one that was rising, rising green and grave behind us. He taught me how to ride that first grand wave as together we came back to Mommy. I pulled her to come but all she would do is stand at the very edge, small waves tugging at ankles. She said, “Reuven, now the ocean is yours.”

By the time I was three, the shaking disease had entered her body, by the time I was four, I knew she stood at the edge of the great waves because she didn’t have the strength to move through them, although I knew once, long ago, she had been a slender fish. By the time I was five, I would offer my hand so she could rise trembling from her chair next to the door that led into the kitchen. But still she would read me stories of brave tugboats, mercurial silkies, mermen and whales, always she immersed me, reminded me of my first great connection to water, the salty seas that surrounded me, nourished me when I laid curled and swimming inside her.

I was a born body surfer. I knew through practice and even more through the grace that comes from loving an ocean.

Surf boards and body boards were just pieces of wood or fiber glass that kept you from really knowing the great moving sea. The ocean was made for bodies, for the shimmering scaled bodies of mackerel and herring, for the mighty sword fish, for dolphins, whales, brine shrimp, for sharks, for squid, for the summer tanned body of me.

I went alone into a still near freezing Atlantic by mid-May and I returned day after day to be held by the water until the harvest moon of October. I knew when to dive beneath a rolling breaker, dive deep to keep from tumbling back onto the beach, dive to miss a left catching current, a rip tide; I knew how to follow the ocean far out, as I waited, waited for the great surge of water that I could ride back to the beach..

I was the bane of the life guards because I was little, a skinny shrimp of a boy and I could be far into the ocean before they ever saw me. The life guards would finally spot me, belly bourn by a wave and then emerging from the water standing, upright while the muscled teenage boys on tall white-painted wooden platforms were shouting at me because of rough water, the remnants of a hurricane or a shark warning. A life guard would leap from his high seat, chasing me as I turned and disappeared beneath the next wave.

After awhile, they left me alone except to place bets on me. I could out-swim them, I swam past all sense of safety, I swam into the shipping lanes on a fair day with a warm sun. And always I came back, nearing dusk, riding a night arriving wave, knowing my mother’s late dinner would be waiting on the back of a still summer hot stove. I would come home and whisper ocean stories to my mother, my first ocean.

After all of my family was asleep and the high school boys and their girls spread their kissing, close body blankets on the dark beach, I came back to the ocean; I came back to danger. Dark creosoted poles, 15 to 20 inches across, and then roped together, made the pilings for the long wharfs that ran out into the water. In the day time it was easy to see them and ride a wave right past but in the dark sometimes I liked to ride a wave a crazy night way through the black alley of water as it pounded between the pilings.

I knew underwater things; I knew them from diving deep and swimming long and hard before rising beyond the breakers, rising for air. I felt at home underwater, no need for words when I was pulled inward, hearing only the boundless full sound of water and movement. I swam into schools of herring, I have seen the long raspy body of the shark and I knew: lay still, float, no motion, nothing to give away that I am alive, moving, warm. That stillness, necessary to keep living, was spurned in my heart, because I would have rather been swimming along side the shredding and tearing beast and learning shark songs from long before any thing moved upon the earth.

I loved being beneath the water, practicing holding a longer and longer breath, swimming out with the tide, seeking a downward spout, swimming down through it and up into a watery birth that could just as easily be a grave if water, spout, tide and breath was misjudged.

I knew the pendulum in water that swings: life, death; life, death in a way that never seems so present, so possible on land. And at the same time, the water rocked me in an eternity, a moving, suspended forever, broken only by my lungs burning, insisting on air.

I loved being supple on the crest of a breaking wave. I was pulled into two kinds of daring, daring the water to hold me within her forever and daring every wave I was riding, to fling me unconscious and broken onto the beach.

As a man and a father, I would teach my daughters the secrets of the ocean. I taught both of my girls to dive beneath a breaker, to swim way out and then how to tell which swell would rise to be a wave that would carry them in. I taught them that it was a finer art to use your body upon a wave rather than a board. They learned, they remembered.

Now I am dead nearly thirteen years. My heaven is water; it is the sea, now I am learning shark songs, now I am swimming beneath; now I am slicing a Far Rockaway wave.

Heaven, if it exists, takes us home and sets us free.

—————————————————— Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.

One Comment

Dear Annie,

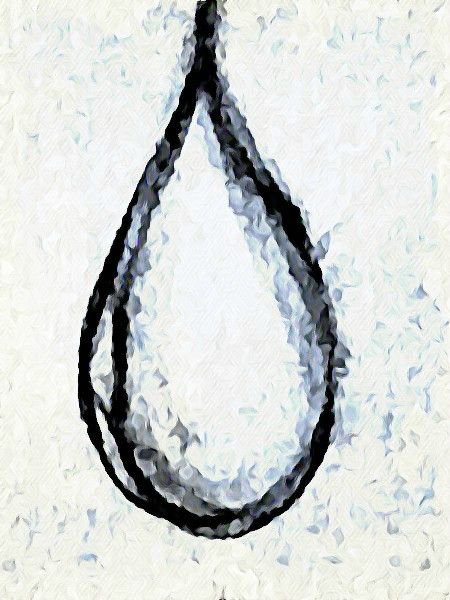

The water-drop is exquisite and reminds me of oceans in a drop of water. It also seems to contain and speak to my husband. Thank you. I had trouble with the posting process but I did send your powerful inspiration piece and my response to Amy and, if it is not yet up, it will be shortly.

In the meantime thank you for such a perfect and evocative image. When I see it, I realize nothing else would do. Not only is it the essence of Reuven’s ocean, it is also the tear in response to the loss named in the writing.