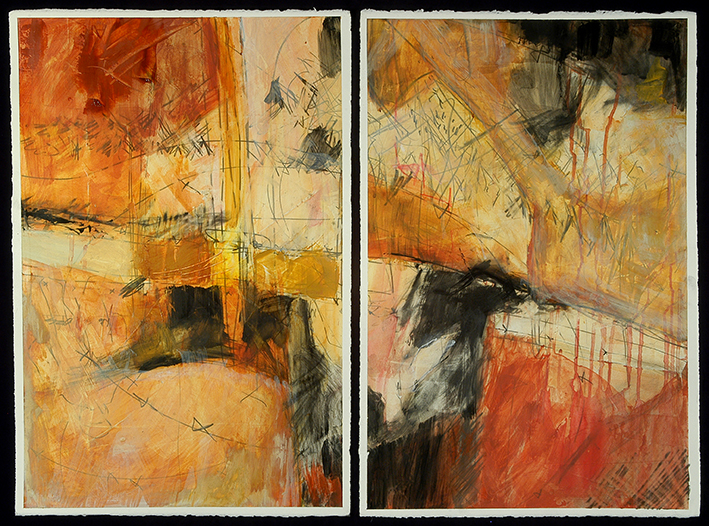

Ghost Prophet by Denise Marois

Response

Lilly thinks the old woman has nodded off. She’s been sitting still for almost an hour, only the slightest rise and fall of her shoulders says she’s even alive. The woman, Mapiya Lapahe, is hunched over the table in the corner by the fireplace, her hands pressed to her forehead. Although the heat is oppressive inside the small room, the fireplace is going and smoke scented with sage and cedar fills the air.

Suddenly, Mapiya Lapahe looks up at Lilly, smiles exposing jagged teeth. Her hair is the color of slate and stone, pulled back in with pink elastic. Stray wisps fall across her forehead.

It is full noon and the sun is directly over the house. The heat presses against the walls, leaving Lilly lightheaded, her fair, freckled skin scorched, her throat dry from the long walk up the ragged dirt path to this slat-sided, crooked place where Mapiya Lapahe, lives. She has come here against her father’s warning that the New Mexico desert this time of year is too hot, come for answers that have yet to be forthcoming.

“Don’t ask questions,” Troy Tsosie cautioned as they set out that morning. “Grandmother Mapiya doesn’t like questions. She says the bones will tell the story.”

“Where does she get the bones?” Lilly is nervous at the thought of seeing human bones. She doesn’t want to look at the evidence of death, the detritus of a person who lived, walked perhaps where she walks now, reduced to a pile, no better than dead tree branches, for telling fortunes and talking to ghosts. She doesn’t really believe that Mapiya Lapahe can talk to ghosts. She thinks it’s a story shelled out to white tourists, the B grade movie shaman who lives in the middle of nowhere and communes with the dead. She can hardly believe she’s agreed to come here at all.

“They’re cow bones, actually” Troy says. He is taller than Lilly, and she struggles to keep up. After a while, he slows, matches his pace hers. Troy is 17, a year older than Lilly, with black hair that sweeps over his ears. He has a scar that runs from his ear, down along his neck to his shoulder. His father put it there, an accident, but Jim Tsosie is serving time anyway. When he cut his son, he was trying to murder his wife.

Lilly thinks Troy, with his black old soul eyes and crooked grin, is the most beautiful thing she’s ever seen. She even finds his scar fascinating. The boys she knew at school in Fairfax, Virginia, are shadows against a gray backdrop.

Lilly is slight, with dark auburn hair and pale green eyes flecked with gold. She wears thin sneakers without laces that flop on her feet, and cut-off jeans that ride high up on her thighs, exposing the white vulnerability of her flesh.

She has defied her father’s orders to stay home on this day, one of the hottest of the summer. But Troy claims Mapiya Lapahe is the real thing, and she has never agreed to help a white person. She does not share her gift with tourists. But Troy has asked it of her. Mapiya Lapahe is ill. The doctors want to put her in the hospital. She refuses to leave the house from which she has not wandered more than a few hundred yards since her husband died 30 years ago. Troy says she already has one foot in the spirit world.

It’s been almost a year since a drunk driver in a suburb outside of Washington, DC took her mother’s life. Lilly’s father, Sam McCallister, took the sheriff’s job in a small New Mexico town when the offer came from an old friend, because he thought the change would help Lilly cope. But she’s still inundated with waves of grief. At night, Lilly lies in bed, willing her mother to come into her room, to feel her breath on her cheek as she kisses her goodnight. In the morning, she thinks she can smell of her mother’s gardenia perfume.

At first, Lilly hated New Mexico, hated the hot days and the freezing nights, the strange tortured animal sounds that haunted the air. The brilliance of the sky, the flatness of the landscape frightened her. The fiery orange and sun soaked blue of the desert singed her eyes. The air sucked the water from her skin, the wind blistered her lips.

She spent hours drawing faces in the sand with a stick like a child, gave them tear-stained cheeks and downward turned mouths. In the summer, she went to Troy’s mother, Sally Tsosie, while her father worked the day shift, so she would not sit alone in the house and brood.

For the first few weeks, Troy sat on the porch watching Lilly draw her sad sand faces. He drank lemonade, hot air snaking up around his bare feet, his arms turning a deep copper. Then one day he came to sit beside her and, taking the stick, drew a horse and rider, then a coyote with bared fangs, and then a woman with a gardenia in her hair.

“I’ve seen her,” he said, tapping the stick at the woman in the sand. “Walking beside you.”

Lilly stayed in bed for two days after, refusing to go to Sally Tsosie’s house, shivering in the heat under the blankets, terrified to walk out the door. Her father called home every half hour to make sure she was all right. “I can’t keep doing this,” he said. “Sick or not, you have to go to Sally’s.”

But on the third day when she again refused to go, Troy drove up in his mother’s jeep.

He strode into the house like it was his own, bringing electricity on his skin. He wore a white shirt with the sleeves cut off over faded jeans with holes in both knees, and snakeskin cowboy boots.

He sat on the sofa, leaned over and stared at Lilly. That was when she noticed his eyes, how black they were, saw the old soul that looked out of them. Her heart beat in her throat, but it was no longer from fear.

“Tomorrow,” he said. “I’ll take you to see my grandmother.”

“Why,” she said. “Why do you want to take me there?”

“She can help you.”

“I don’t believe in ghosts. I don’t believe in shamans and talking to dead people. My mother is gone. She isn’t coming back.” She brushed tears from her face.

“I know,” he took her hand. “But come anyway.”

With the feel of his palm, dry and smooth, pressing hers, she could not refuse.

It’s taken an hour’s ride in the jeep and another half hour of walking in the heat on a road so narrow and rutted even the Jeep couldn’t navigate, to reach the house that sits crooked under a sagging roof. Scrub brush dots the yard, which is otherwise bare.

Now, Lilly still has no answers, only that that she should have worn boots and not her thin sneakers that are not designed for walking in the desert.

The bones are yellow and silent on the table. Mapiya Lapahe does not move. The fireplace burns high, the smell of sage and cedar settles in her nose like hot ash. Sweat spills down her cheeks. She stands in the open doorway, where a dog sleeps by a pile of scrub. The heat of the fireplace, the parched desert air, make her feel sick. She tries to step outside, but floor moves and her legs give way. As she falls, she feels Troy’s arms around her waist. When she opens her eyes, she is stretched out on the floor.

The old woman is kneeling beside her, smiling her jagged toothed smile. The sun has moved out of the doorway, and gray shadows play across the ochre walls. From somewhere out on the plain, an animal sends up its tortured wail. Troy lifts Lilly’s head, puts a bottle of water to her mouth. She takes long, thirsty gulps, sits up, her head throbbing. In the corner, one shadow seems to separate itself from the others, floats for an instant, then vanishes. Lilly is not certain it was ever there.

Mapiya Lapahe runs a calloused hand over Lilly’s head. She points out to the rutted road that leads to her house. “Love walks beside you,” she says.

“I don’t know what she meant,” Lilly and Troy make their way along the road, toward the jeep, step carefully over the ruts. The cooling night clears her head, the weakness in her legs and throbbing in her head are gone. But she feels empty, let down. Then, a breeze comes out of the stillness and touches her cheek like a kiss.

Troy looks at the ground, smiles in the growing dusk. He takes her hand.

“Give it time,” he says, his fingers intertwine with hers. “Just give it time.”

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.

One Comment

What a vivid, compelling world in this story. I admire the finely-detailed writing immensely.