Lisa Kilhefner

Inspiration Piece

Truman’s House of Flowers

By Jenny Cutler Lopez

Response

I leave a late, cold spring to fly to central Alabama where the grass is already a florescent green and the bright air buzzes with crickets. Until the sun sets on its clay roads or the clouds sweep up from the Gulf of Mexico, Alabama’s light is crimson. Just as all places possess a particular light: the bone-white Bahamas, the sepia of Virginia Beach.

I consider heat as claustrophobic as a bully so in Monroeville I linger anywhere blessed with cool air. The fetid hotel lobby; the crisp college library; run-down cafés; my rented car; and shady groves in which I drink sweet tea. I linger in the old courthouse downtown and there I discover a one-floor museum divided in two. To the left, a room dedicated to Monroeville’s queen Harper Lee. To the right, a room dedicated to the queen’s Rasputin: Truman Capote.

The air-conditioner is on the fritz but the lazy ceiling-fans work well enough so I amble, reading the what’s what of Lee and Capote. Truman lived a half-mile from the courthouse with distant relatives for five years. His mother abandoned him to the elderly Faulk siblings: three aunts and one uncle, when Truman was four. One of the spinsters, Sook, so loved the boy from Louisiana, Truman pronounced her, his best friend. Sook was a white-haired, slightly crippled, dog-loving snake-killer, snuff-chewing japonica-gardener, a story-telling homebody.

I exhaust the museum. I poke around the gift shop. I sign the guest register. I strike up a conversation with George Thomas Jones. Jones is 92 years old, a lifelong local of Monroeville, and he tells me this story.

“I was jerkin’ sodas one summer in the soda shop just around the corner from here. Capote was 11 or 12. I was 15. He was a runt. Skinny with a high-pitched voice. None of the boys liked him. But he had a bodyguard, you see – Nelle (Harper) Lee. And I had told the other boys that they ain’t ever gonna whip Capote with their words and win cause he’s too damn smart.

Well, it was a blazin’ hot July morning when the door opens and in walks Capote. He walks up to the counter and flops down on a stool in front of me. He flipped this big straw hat up and out of his face and looked at me. He let out a long sigh.

‘What can I get you?’ I asked him.

‘I want something special, but you ain’t got it,’ he said.

But you see, I prided myself on knowin’ how to make just about any drink so I said to him, ‘You tell me what you want and I’ll make it for you.’

Capote looks at me and he says, “I want a Broadway Flip.”

Well I ain’t ever heard of such a thing. I leaned over the counter right up to him and said ‘You better watch it boy or I’ll flip you right off that stool.’ Capote jumped off the stool and ran out that door as fast as could be.”

Nobody in Monroeville has much good to say about Truman.

Earlier that day, at a reading of Truman’s House of Flowers, the audience titters when a local pronounces, as an adult “Capote had… peculiar tastes,” and how “he became very familiar with everyone he met.” Another man tells me stories starring Capote as a flouncing, obnoxious child.

Abandoned and scared; too short, too clever; too effeminate; an outsider. How did this young child know not to compromise his essence, no matter how lonely or rejected he felt?

The next afternoon, I sit in in a room made from white stone and tall windows at Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Montgomery home. A soft green light, a jasmine-scented breeze, old photographs and flowers everywhere. A place where loneliness blossoms into peaceful solitude.

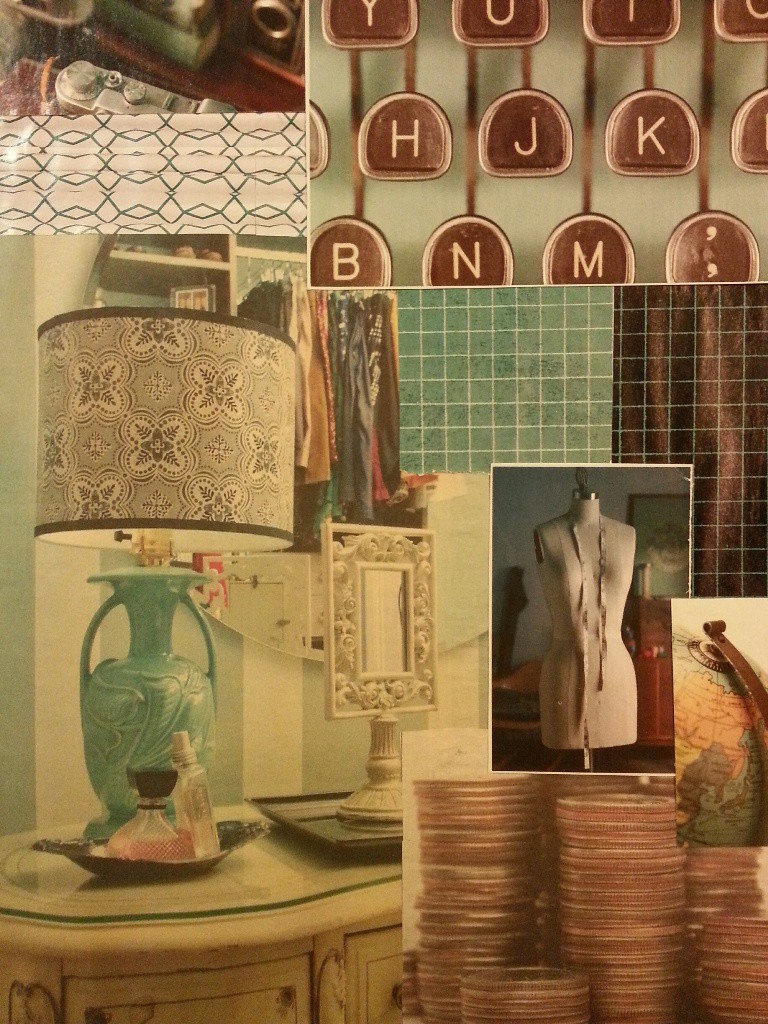

Is this what Sook’s home meant to Truman? Was it restful? A sanctuary? I imagine two floors of cluttered rooms filled with a dusty busyness and half-finished jobs-for-money: an unhemmed dress on a seamstress mannequin, a pile of ironed laundry, nails and hammer next to a bed frame. I imagine a sunlit room, a set of scalloped hand-mirrors and hairbrushes. Blossoms creep across an open window. Atop a colorful quilt on a bed rests Truman with his book, a pencil, some paper. He exhales. These walls and Sook protect him from life out there. And she protects him until he is nine and his mother whisks him to NYC to live with her and his new stepfather.

I don’t want to leave the Fitzgerald house but there’s a plane to catch. A life of negotiation and noise and lists whine my name. The memory of this leaf-filtered silence will soothe me on taxing days. Just as Truman returned to Sook’s house in his fiction. Just as we all hold onto places made from a special light.

—————————————–

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.