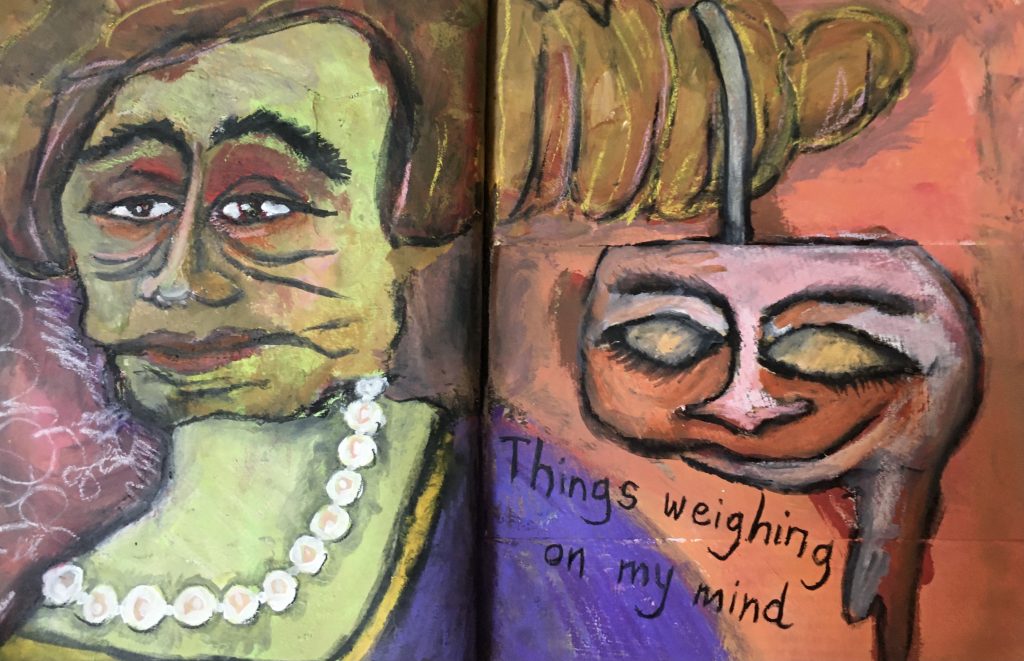

Erika Cleveland

“Things Weighing on My Mind”

Inspiration piece

The Weighty Decades of Yehudis Blau

By Channie Greenberg

Response

Yehudis sighed as she pulled at her cuticle. When she was a child, she used to chew that flexible bit of her flesh until her mother started doctoring it with Tabasco sauce. Later, as a teen, she became a nail-biter. Unfortunately, that latter behavior, i.e., her nipping at the flattish horns on her fingers, did less to alleviate her anxieties than had her former one of tearing the nonmineral covering situated at the base of each of her nails.

It was of little wonder that adolescent Yehudis felt so much tension. Her older brother, Asher, had drafted into the IDF as a lone soldier. Mere months after his enlistment, the Six Day War had erupted. Despite Israel’s air supremacy, too many soldiers died defending the Holy Land. Yehudis, like her mother, became very upset.

Providentially, at the time, Shlomo Errel was the chief of Israel’s navy. During the Battle of the Rumani Coast, he was instrumental in sinking of two Egyptian torpedo boats and in preserving the lives of all of his men. Shlomo was smart. He was confident. He was a great strategist. He was also Asher’s mentor.

In 1968, Shlomo retired from the IDF and moved to New York, where he studied at Colombia. Asher, likewise, left Israel to relocate to Gotham.

Shlomo married Sara, who birthed their children, Gilia and Udi. Asher married no one and fathered no children.

Rather, Asher applied to work at the help desk of Barnard College’s Information Department. Notwithstanding his acquaintance with many of that school’s collegians, he remained a bachelor.

On balance, Asher used his free hours to manipulate the school’s large, mainframe computer. When, in the early 1970s, Barnard invested in an Intel 4004, a state-of-the-art microprocessor, Asher was among the limited number of staff members permitted to use it.

Elsewhere, Yehudis aged. Her mother kept increasingly pressing her to marry and to produce the family’s next generation. Little was said about Asher’s singlehood. Contrariwise, Yehudis’ mother asked her to relocate to The Center of the Universe since the selection of “nice, Jewish boys” in New York, purportedly, was better than was the selection of “nice, Jewish boys” in their “out-of-town” city, Pittsburgh.

Yehudis set aside her mother’s protests and stayed put. The profit that she made on some stocks and bonds enabled her to leave her dull, management position at Westinghouse Corporation’s headquarters and to open a flower shop on Squirrel Hill’s main street.

To her great joy and her mother’s chagrin, Yehudis’ business became a terminus for party planners and locals. Her shop provided ambiance for bnai mitzvot and weddings, as well as for baptisms and confirmations—then, as now, Pittsburgh was largely a Catholic metropolis.

When Yehudis reached thirty, her mother hired a shadchan, i.e., a matchmaker. Whereas their family wasn’t Orthodox, Asher had been spending more time in hospitals, where he sought drug cocktails and other treatments for his recurring HIV complications, than in Barnard’s budding Information Technology Department. While, with great hoopla and little enthusiasm, Yehudis had at last agreed to date Boaz Haddad, then Netanel Weiss, then Hirsh Levy, and, finally, Shay Efron, Asher’s CD4+ count was hovering in the low 200s. An AIDs diagnosis seemed imminent. Thus, unless Yehudis soon wed, her mother would have no grandchildren.

Yehudis married Shay, but their union produced mixed mazel. On the one hand, he planted two sons and two daughters in her womb. On the other hand, their children grew up with a father who leaned on a cane, then relied on a walker, and, in the end, couldn’t ambulate unless someone pushed his wheelchair. Initially unbeknownst to Yehudis, two decades prior to their nuptials, Shay had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. The man who, in the past, had carried her over their apartment’s threshold, spent the remainder of their shared decades in decline.

In the first part of her and Shay’s time together, Yehudis and her children rallied, aiding him with eating, dressing, and using the bathroom. As those offspring grew into teenagers, all the same, that arrangement stopped working. One son flew off to Israel to enlist like his uncle had earlier. Another entered a graduated program on the West Coast. As for the girls, they objected, rightfully, to having to continue assisting their father with his bodily needs.

The younger daughter sought a “safe” escape. She applied for and was granted early admission to college. The older one moved to the commune that had been suggested to her by her Uncle Asher.

In due course, Yehudis hired aides. She drained all of her and Shay’s savings, investments, and other monies to paying for his care.

Within a season of her selling their house and moving them into a rental, Shay died of a pulmonary infection. At only sixty, Yehudis was widowed. She had no home, no nearby kin, and no flower store (her business, as well, had been sold to pay for some of Shay’s medical bills.)

Yehudis weighed moving to a senior community in Vallejo or sharing an apartment in West San Jose with a junior roommate, but the Bay Area’s cost of living, the lack of jobs being offered by eBay, and the commute between either of her dream locations and Stanford University forced Yehudis to give up on living near her son. Instead, she retired to Cape Coral, Florida, where she parleyed the accounting skills that she had developed as an entrepreneur into a part-time gig with the Fort Meyers branch of the IRA.

Yehudis spent over two hours getting to and from work, daily. In spite of that time sink, she reveled in the beauty of her canal-laced city, was happy when walking along Cape Coral’s beaches, and was thrilled by the Caloosa Bird Club’s activities. So, she stayed put in her light-filled, nearly affordable studio.

Her apartment stopped being within her means, however, after she underwent a hip replacement that necessitated her paying for help and after her insurance provider refused to cover the cost of replacing the items that had been stolen by her nurses. Yehudis began to contemplate her younger daughter’s suggestions that she return North to live in the unit adjunct to her daughter’s house. All that Yehudis had to do in exchange for the use of that residence was to babysit her five grandchildren every day, cook dinner on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays, and serve as the family’s laundress every Monday and Friday.

At the outset, it appeared that Yehudis had no better alternatives. Her son at Stanford was busy with postdoc research. Her once commune-bound daughter, that child who had meanwhile served in and then left a Peace Corp position in agroforestry, in Africa, was occupied building Earthships in New Mexico. Yehudis’ youngest had stayed in Israel. He had made aliyah, married a girl from Holon, and was pursuing a Technion degree in Education in Science and Technology (like his brother, he was proficient in math.)

What’s more, Yehudis’ mother was dead, having hung on long enough to behold great-grandchildren, but not any longer. As per Yehudis’ brother, Asher, he was still very much alive, still very much employed by Barnard, and still very convinced that his sister and his lifestyle ought not to intermingle.

Yehudis picked at her cuticle, again. Mandatory retirement had, essentially, been abolished by the ADEA. Even so, employers preferred to hire less expensive, less experienced kids than grandmas like her. Perhaps, in addition to her part-time IRA work, she could become a greeter at the local Walmart Supercenter. Perhaps, she could teach EFL online. Perhaps, she should take a short walk into the ocean during high tide.

Yehudis actualized none of those options. Equally, she did not move to the unit attached to her daughter’s house. In lieu of those schemes, she decided to get remarried.

Much as women considerably outnumbered men in her cohort, in the local dating pool, Yehudis successfully spent time with Barry Zangwill from Pine Manor, then with Yossi Felman from San Carlos Park, then with Yitzi Zander from Fort Myers Beach, and, eventually, with Avi Steingart from Burnt Store Marina. She hadn’t intended to swipe right on Avi as, unlike her other suitors, he was a divorcee, not a widower, but something about his self-description had made her smile.

Avi had referred to himself as “bald, aging, and possessed of a quirky sense of humor.” He had, moreover, indicated that regardless of the reality that his assets were generous, two sets of alimony payments left him with relatively modest day-to-day means.

Yehudis reckoned that anyone living in a yachting resort couldn’t be objectively poor. She agreed to date him, anyway.

During their House of Omelets first date, Avi stated that his wealth had been made from “investments,” e.g., from Topps Chewing Gum baseball cards. Later, he had progressed to buying precious metals and real estate. His last dealings had been with CDs and TIPs. Venture capital had never been on his radar. Further, he no longer dallied with his resources as he had no incentive to become richer.

Avi brought Yehudis to The Trading Post, for ice cream, for their second date. For their third date, he escorted her through the Imaginarium Science Center. For their fourth date, he joined her at Harbor View Gallery. For their fifth, he invited Yehudis aboard to sample galley-sourced cooking. That night, he proposed.

Subsequently, neither of them thought it necessary to seek their children’s permission to marry. Equally, they felt no need to delay their ceremony; they were getting more and more elderly each day. Their simple service involved a civil servant, and, as a witness, a pal from Yehudis’ birding club.

After a few kisses and cocktails, they returned to Avi’s boat. To create a fresh start for his new bride, Avi had had his vessel moved to a berth at Sanibel Marina. Correspondingly, he had given Yehudis an allowance to redecorate it. Its interior walls sported blue paint, not white. Its floor, which once had been covered with cork, was now carpeted.

For her part, Yehudis quit her IRA job; Avi deserved her full attention. She learned how to rub the cricks out of his neck. She learned, too, how not to complain when he asked her to dress and cook the fish he enjoyed catching.

A few months into their marriage, the pair made a trip to Israel so that Avi could meet his younger stepson and so that Yehudis could meet her newest grandchildren. Shortly thereafter, Avi was felled by a heart attack.

Following Avi’s death, for almost a decade, Yehudis lived alone on Avi’s yacht. Because venturing out meant the possibility of encountering the snakes that the local government had encouraged to breed, to reduce the area’s rodent population, she relied on delivery services for food and other staples. Likewise, Yehudis paid an excessive amount of dollars to have her garbage and gray water carted off and to have her tanks topped.

In the interim, Yehudis met and became friends with both of Avi’s former wives. Those ladies sincerely thanked her for befriending the man whom they had loved but had found impossible with whom to live. He had never been a womanizer, a drunk, or irresponsible with money, just extremely unconventional.

Neither of those other women had appreciated his insistence on using only complimentary medicine or on wearing only Hawaiian shirts. Additionally, each of them had detested his lack of involvement in local galas, specifically, and his refusal to sell his boat to live life ashore, more generally.

All things considered, the differences between Rachel and Sara, and Yehudis were unimportant. Rachel, Avi’s first wife, brokered peace between Yehudis and her now food forest-championing daughter. Avi’s second wife, Sara, coaxed Yehudis’ older girl to visit Florida unaccompanied by her husband or children. At Yehudis’ funeral, that offspring wouldn’t stop babbling about the wonderful, solo vacation that she had taken “at her mother’s behest.” Those triumphs aside, all of Rachel and Sara’s attempts to reconcile Asher and Yehudis failed.

At least, those three ladies enjoyed their cross-country trip. Together, they drove from Florida’s West Coast to Stanford and back.

In California, two truly proud aunties, Rachel and Sara, oohed and aahed over Yehudis’ boy’s accomplishment. They plied him with contact details for their friends’ daughters and for their own nieces. A few years after Yehudis’ death, that fledgling scientist married one of their nieces, a gal who had been working as a software engineer in Palo Alto.

Toward the end of Yehudis’ life, Rachel and Sara took turns supervising her nurses. Cancer had made her frail. At the same time as those women detested Yehudis’ home’s rocking and pitching, they loved her. In fact, both ladies were at her side when hospice care said it was time for “Viduy.”

Asher came down from New York for Yehudis’ funeral. All of Yehudis’ children and all of her grandchildren, too, made themselves present. Discretely, Rachel and Sara photographed her family.

Ultimately, those two silvered-haired ladies bought Yehudis’ boat from her family. After a long wait, they had found a good use for their stockpiled alimony payments.

They would remember Avi. They would remember Yehudis. Over and above those veracities, they would embark on a final adventure. A call to a nearby drugstore would supply them with dimenhydrinate and cyclizine. A call to a sea recruitment service would yield them a pilot and cook.

Before the ladies set sail, Asher asked for and was given a few of Yehudis’ stuffed animals and some of the vases that she had saved from her flower shop. Yehudis’ sons and daughters picked out paintings, tea towels, and other, miscellaneous bits and bobs that reminded them of their childhood. Weirdly, the four of them fought over the catheter that had been left over from their father’s care and that had been discovered at the bottom of Yehudis’ footlocker.

Conversely, none among them laid claim to Yehudis’ fingernail scissors or to her yellowed picture of Commander Shlomo Errel.

For that reason, Rachel and Sara donated those items and the rest of Yehudis’ effects to Good Will. They arranged taxis to shuttle her kin to the airport. Then, they opened a variety of nautical charts.

——————————————————

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.