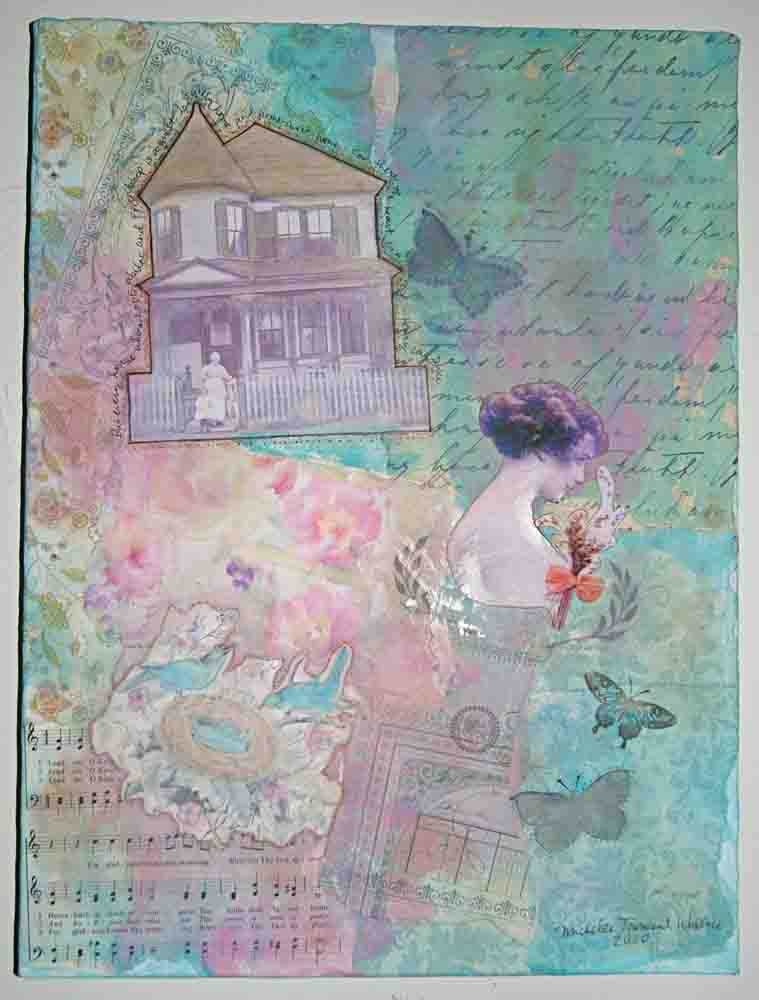

Michelle Wallace

Home Sweet Home

Response

All the Way Home

By Catie Jarvis

Inspiration piece

On the day Hugh returns home from the war, his mother looks so young. She stands in the doorway, dark brown hair gathered up on top of her head, house dress floating loosely around her – airy in the breeze. Hugh feels as though so much time has passed while he was away that he half expected to return home to find her an old woman. But instead she stands before him looking younger then the day he left. She’s tan and lively, hands covered in flour, nails caked with dough. She stares, speechless, as if he were an apparition she were savoring. As if any word or motion, even the blink of an eye, might make him disappear.

From Vietnam, Hugh was flown into DC like all the soldiers. They clean him up and give him a stiff new uniform. What he wouldn’t do for a T-shirt, a loose baggy cotton shirt that says “Free at Last!” They offer him a hair cut, but he doesn’t take it. He’s growing his hair out. He pets the short strands on his head encouragingly. They offer him a steak dinner, and he laughs: “Man, I don’t want steak, I just want to go home.” But the steak dinner isn’t like the haircut, and he can’t opt out of it. Hugh enters the mess hall with the other guys like him, fresh into the country. They all look familiar but he doesn’t know any of them. He eats his steak in silence and it turns out to taste pretty good.

At National, Hugh books a flight out to Kennedy. Luckily, there’s a plane leaving soon. He’s carrying a small bag that he keeps misplacing. Every time he goes to the airport restroom or gets a bite to eat or switches his chair because the sun through those large paneled windows is getting in his eyes, he almost leaves the bag behind. There’s not much in it anyway. A few pictures. All the letters his mother wrote him. A necklace, cheap and tarnished, from a girl he found out in the jungle infested with flies and hardly alive. A few pieces of foreign currency that he wants to give to his sister because he knows she’ll like that sort of thing. Somehow, Hugh still manages to have the bag with him when he makes it from Kennedy to Grand Central Station, and onto the side of the highway in Patterson New Jersey where routes 208 and 4 collide. He throws the bag over his shoulder, now glad that he’s kept it, glad he has something to posses. He holds his thumb up.

The wind and exhaust of cars blows at him and he sucks it into his lungs. They fly by, he thinks. He keeps on thinking that: They fly by. They fly by. He decides he won’t mind if he has to stand out here by the highway all afternoon, even all evening, and into the night. What’s the hurry anyway? There’s nothing for him. His thoughts start to compile and plummet into some kind of plan – the kind in which he’ll never make it home. Luckily, before the thoughts get too far, a woman in a nice town car pulls over and right up to the side of his legs.

The woman is slender and middle aged. She has a wispy layered hair cut, her make-up is neat and refined. He thinks of her first as a woman and is surprised by the thought. She’s the age of mothers, his mother, his friend’s mothers, but it feels like that doesn’t matter any more. Hugh has trouble picturing what he must look like to her. A kid? A man? A lonely solider?

“Where you headed?” he asks her before she gets a chance to say anything. He doesn’t want to send anyone out of their way.

“Wyckoff,” she says.

“Yeah. That’ll work.”

Inside, the car smells new, leathery and stifling.

“My son’s in the air force,” she says first thing. Now Hugh knows just how she pictures him and he feels relieved. “When did you get out?” She asks.

“Well today. I just flew in today.”

“My goodness. Welcome home, honey. I’m sure you mother will be so thrilled to see you.”

She pauses and sighs into the steering wheel.

“Your son, he’ll come too,” Hugh says.

“Will you tell me what it’s like?”

They are driving in the right lane, slow, so that cars keep passing them. One car gets right up behind them and honks it’s horn. The woman doesn’t seem to notice or at least not to mind.

“It’s not like you see on TV,” Hugh says. “It’s not chaos all the time or anything like that. They’ll be some bad days, shots fried, explosions, some civilian detonating a bomb and screaming. But then for weeks there’ll be nothing. Silence. Card playing. Tucking in the sheets. It’s not all crazy like you see on TV, and it’s not all bad. Your son, he’ll be all right.”

“His name is Ryan Ellington. Haven’t heard of him, have you? You wouldn’t know him, would you?”

“I don’t know him.”

“Where’d you say you were going again?” She asks.

“Oh you can let me off in Wyckoff, that’s fine. I’m only a town over, I can walk home from there.”

“I’m bringing you home,” she says. “All the way home.”

They sit in silence for a while, feeling the bumps of the road. The woman flicks on the radio and turns it down about as low as it can go and still be heard.

“Honey, why were you out there by yourself, on the side of the highway?” She asks in a whisper. As if this question is a secret and she’s scared to know the answer.

“When you come home,” Hugh says. “You come home alone.”

The woman takes her hand off the steering wheel and pats him on the arm. The car takes a slight swerve. Hugh is afraid that she might start to cry. In fact, he’s petrified. He thinks if she starts to cry he’ll have to get out of there, open the door, jump and roll. He has to say something to snap her out of it.

“You know how much it cost me to take a cab from Kennedy to Grand Central?” Hugh asks.

The woman removes her patting hand from his arm and says, “No?”

“Cost twenty-six dollars. For a cab ride. You believe that? I can’t believe it. I think I’ll always remember that number, twenty-six god damned dollars for a cab ride.”

Hugh’s voice has grown loud, too loud. The woman leans towards the steering wheel. They turn off the highway and Hugh directs, saying every few minutes, “We’re just about there, drop me anytime.” He’s still saying this when they pull right up to his street. He’s still saying it when they pull right up to his driveway.

“All the way home,” the woman says as she breaks mid way down Hugh’s long rocky drive.

The farmhouse looks sturdy, white, maybe it has a new paint job. The leaves have turned and the yard is colorful with yellow and red leaves, orange tree’s. It’s pretty much Thanksgiving by the look of it, with his mother’s decorative hay barrels and hardened purple corn stalks on the porch. Hugh walks up his driveway in a slow straight line. He’s nervous like some Charlie’s fast approaching. This is the home he’s been dreaming of for 18 months, here he is at last, and still he can’t seem to get back that old feeling of safety. He climbs the granite slab front steps, unsure of the kind of hurt he might find.

His mother stares at him for a long time before she takes him in her arms and allows him into the house that smells of baking bread and damp carpets and home. He’s afraid to sit down on the couch, to lie on his bed, he’s afraid of what will come to mind, afraid that it will all disappear, the mother, the bread, the house, all of it. He walks around from room to room, waiting for the rest of his family to arrive home, to fill the house with the distractions of their sound. He walks up the stairs and back down, from the kitchen, to the living room to the den. He looks out the window and sees that the woman is still sitting there half way down his driveway. She is staring right into the house as if it were her own house, as if it were her son who’d come home.

.

.

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.