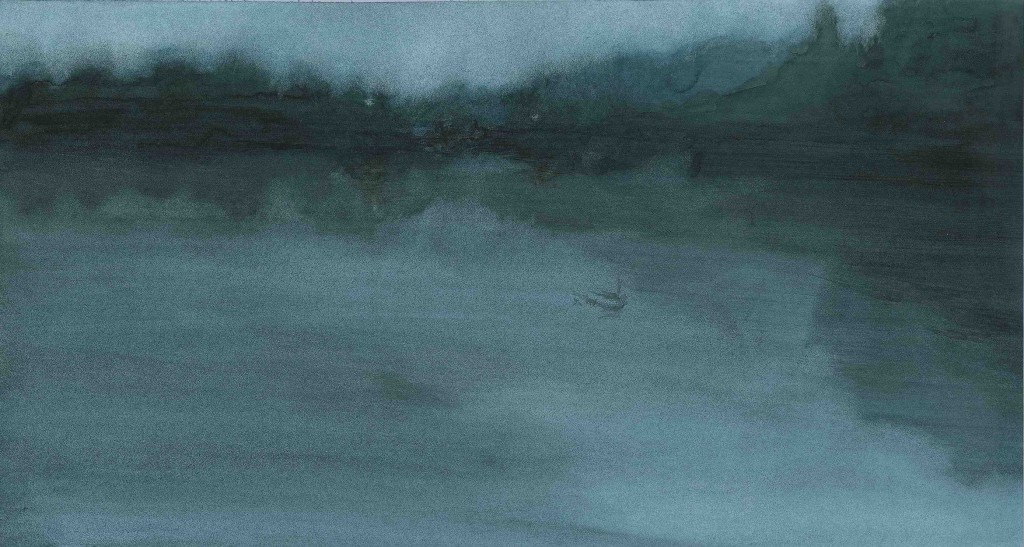

Nocturne, Saugutuck River

Matthew Levine

Inspiration

The Gloaming

By Robert Haydon Jones

Response

“You can’t beat this view,” Paul Robinson said. “I can see up and down the river right from here. There are a lot of people in this city paying $1,000 a night who would much prefer this view.”

I couldn’t argue with him. I was sitting right by his bed. I could see up and down the mighty river.

“One of the big shots who financed the hospital insisted they allocate ten riverside rooms as a hospice. I forget which robber baron it was – Vanderbilt, Carnegie, or maybe Haughton.

“Anyway, they say he checked out from up here himself. I’m only in here because I won a lottery. Otherwise I would be in one of those big drab places off York Avenue. I guess you could call me lucky.”

He leaned back and rested his head on the pillows. He really didn’t look all that bad to me. Paul was 84. He looked tired. He looked like he was 84.

He was wearing a NY Giants, Giants-blue, sweatshirt and black cashmere, Zegna, workout tights. His slippers were parked carefully just under the bed. They were those elegant, cordovan, bedroom slippers Brooks Brothers used to sell back when they were still Brooks Brothers.

Paul is 6’4” and still well muscled – a big, handsome, Irish looking man, with a leonine head. His red hair has gone silver, but it is as curly as ever and he still has the two dimples that make the ladies smile even when they know better.

He had been a terrific rugby player in college – and big league teams were scouting him as a lefty pitcher when he broke up with his girl friend and enlisted in the Marines. After he came home, he returned to Yale and went on through Wharton and on to his family’s investment bank.

I met Paul on a rugby pitch on Randall’s Island in New York City. He was the assistant head coach of a famous rugby team from New York that recruited me. He was just six years older than me, but he taught me a lot about rugby and about life. We had stayed close ever since. We had much in common. We were egomaniacs with inferiority complexes. We had been abject failures as rogues. For the last 51 years, we talked to each other nearly every day.

I had known all about Paul’s brain tumor for several years. It was a big tumor – the same kind that killed Teddy Kennedy. Fortunately, Paul’s tumor was benign.

Every six months or so, the surgeon would have at it with a cyber knife. It was no big deal for Paul. “Let’s talk about my brain tumor,” he would say. “It scares everyone when I say ‘my brain tumor.’ I get a perverse sort of pleasure saying it and watching people freak out. I have to admit I say it more than I should. ‘My brain tumor.’ ”

So, I was shocked when Paul called me right after dinner yesterday evening and told me he was in the hospice. “It’s jumped me,” he said. “The doctor says I’m sliding fast. I’ve got maybe a couple of days. He says it might be hours. Nothing can be done.

Don’t argue with me. Get over here right away. I just checked in – so now’s the time for us to have some private time together before Betty and the children and grandchildren and all my friends and admirers come crowding in. Come right now – and bring your box.”

Twenty years back, Paul and I had joined an “Awareness Circle” for recovering men. Every member of the circle was required to build a “found objects” collection and bring it in a box to the circle. Actually, these found objects boxes turned out to be pretty much the same as the collection boxes Paul and I and most other 12-year-old boys had back in the day.

The circle had melted away decades ago but Paul and I stayed with our boxes. We had regular reviews at least once a month. Building our collections wasn’t hard. Once you get grooved to looking around every day, no matter where you are or what you are doing, the discipline of searching comes pretty easy.

Over the years, we learned to look through our collections very slowly. We had discovered the really hard part was looking after the fact. Savoring. The initial quest was easy. Just finding something only took one look.

It was when we formally inspected each other’s boxes that we discovered we were usually in a great hurry to rip through the box rather than to take the time to do the slow see. Everything changed when we realized the big secret was re-looking at the objects we found very, very slowly.

So, I brought my box.

As I sat down in the bedside chair, Paul motioned for me to give him my box, so I handed it over. He whipped off the cover. Then he laid it back on.

“I have a terrible headache,” he said. “But, honestly, I’ve had worse. I’m not sure that the pain is from my brain tumor. I’m angry. I’m very, very angry with my dear friend Doctor Greenburg for not eradicating my tumor. I’m angry at the very nice folks here at the hospice who have just explained to me that this is all about making things as easy as possible for me and my family. I’m angry about being something that gets processed. And, Terry, I’m kind of pissed at you for being in such good health.

“But then again, Terry, I’m distracted. I want to keep paying attention. I want to keep looking. Am I supposed to stop now and concentrate on my death? Look at the sun going down on the river. Am I supposed to ignore that?”

It was a magnificent sunset. Paul was right. It was hard to ignore.

“That’s why I asked you to bring your box,” he said. “I want to review it with you. I want to keep doing the long, slow, looking with you. But I don’t have to open your box – I could do it with the cover on. I know every shell, every feather, every stone, every marble, every arrowhead, every fragment of robins egg in it. The last bit of blue we’ve got left matches that bit of egg shell, doesn’t it?

“I was seven when we moved from Manhattan to Connecticut. To that village by the sea. On the first day I woke up in my new new home, it was bird song and surf sound that woke me up.

“My mother hummed an old Irish song and said the big country stove was a wonder. We had biscuits and waffles and fresh orange juice. As I ate, I gazed out the kitchen window at the backfield. I could see all the way up to Minute Man hill where lots of cows and a horse were grazing.

“Later, as I walked out of the house down the lane and through the sweet-smelling apple orchards and the rolling fields of barley and clover to the beach, I was suffused with a bolt of pure joy that still sparkles in me. I can feel it now.

“The ground aroused me. In those days, I was on the ground a lot, playing pickup four-man football and three-man ‘automatic hits’ baseball in side yards and meadows. After the game was done, I would lie there prone on the ground and the ground would throb under me. And it aroused me.

“I felt connected to the world, as I never had on the cobblestone streets I roamed as a child. All the elements touched me. And I touched them back. I climbed the gnarled apple trees and snatched apples from on high. I scythed hay for the farmer and inhaled the new mown scent. I sloshed through the shallow flats and scooped up clams by the peck and then endured hundreds of nasty cuts learning how to shuck clams and oysters like it was nothing.

“Animals were part of my life – not in a zoo. The amiable cows were everywhere. Often traipsing through the fields, I would startle up a pheasant or a grouse, and every time it made me jump, like I had tripped a mine. I knew three horses by name. Four crows patrolled my field. An owl lived in a nearby barn. Gulls commuted overhead mornings and late evenings to and from the beach. I trapped muskrats for the bounty the state paid. I plinked squirrels for the fun of it.

“In the summer, the salt water dried on me in white crusts. In July and August, working in the fields or playing baseball on a rough diamond set in a pasture, the sun seared me even when I covered up. When, finally, the sun went down it was the best time of the summer. The light was soft and the warmth was soothing and the burn was gone.

“The old people called that time The Gloaming. Owen, my paternal grandfather, sang many a song about the gloaming. About twilight. About love’s old sweet song.

“He strummed a fancy Spanish Guitar. He was 6’4” and had been a boozer and a brawler well into his 60’s –- even at 80, there was still a violent possibility about him as near as his whiskey. At first hearing, his lilting, pure, tenor singing was always an odd surprise.

“He lived in a world in which the only outdoor light came from the sun. When the sun finally sank so far down that it dragged all its beams with it, the world stayed dark till dawn’s early light.

“He told me it was magical to watch day slowly and softly transform into night. At the precise moment that the light slips away, fairies and goblins slip in. He said his grandfather had told him that his grandfather had told him that this minute was the most holy time of the day and night.

“So, Terry, I want you to watch the gloaming with me as carefully as we can – and when it’s full dark, I want you to go and not return. Leave your box. I need it for company.”

We watched together. We sang “Love’s Old Sweet Song.” Shortly after the full dark, Paul fell asleep and I departed.

I’m waiting for word.

——————————————————

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.

13 Comments

Very touching piece. Love this line more that any other “He strummed a fancy Spanish Guitar. He was 6’4” and had been a boozer and a brawler well into his 60’s –- even at 80, there was still a violent possibility about him as near as his whiskey.” Terrific stuff from RHJA.

Love it! Lottery, the slow see, the gloaming. What luck to catch the holiest time!

Matthew~ it’s like looking at a Whistler nocturne. Beautifully Done.

I’ve never thought about how the sun might “drag” its own beams with it till the entire world goes dark. What a poignant verb.

A powerful story. The main character seems very accepting of the fading of light, the passing of his life into darkness. The glomming gives an almost peace to inevitable. Nicely done, nice painting, too.

Nicely written story. Makes you realize how vulnerable we all are, how quickly life passes by, making us grateful for each days gloaming.Grateful for Hospice care too.

Really a story within a story,,,,,,so lyrical,poetic and touching that is skips right past one’s intellect and splashes all over the emotions. A Beauty!

Just a quiet step into eternity and he is smiling forever.A caressing story

What a lovely story. I especially liked the salt water drying on his skin in white crusts. Very sweet and sad…

Thanks RHJ–I haven’t thought of my “Box” in years, and wish I still had it. When getting home in 1953 from The Marine Corps my parents had moved to a smaller house & my Box got lost in the shuffle–no ones fault, but it was gone. How I’d love to have my corn cob pipe that got a lot of use in the early 40’s–smoking corn silk–tea–& even ground up pine needles. Oh how I’d like to take a drag from that pipe of pine needles again! Kids don’t have boxes anymore–everything is in their computer–poor kids. Thanks Robert! You made my day.—Jack

Beautiful and sanguine, I love it! There is much depth and action in this, while at the same time holding the stillness of retrospection.

Beautiful story, beautiful painting. Going to keep working on putting things into the box and remember that each day is a gift. Mr Jones is right; it’s much harder to look at what’s in there. Why is that?

“Roamin’ in the Gloamin'” — Harry Lauder’s old song — comes to mind as a counterpoint to this elegiac beauty.