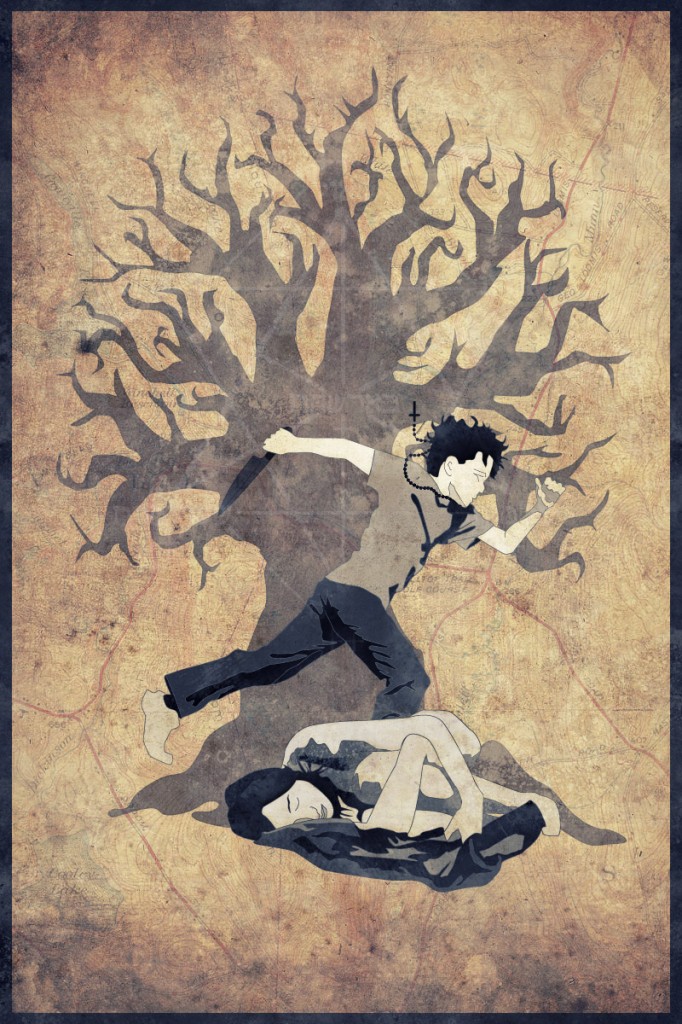

Art response by Blain Klitzke

Story by Daryl Morazzini

Granny Moons

Although poor mountain ministers were not the sort of boys her family would have wished her to embrace, Shell Southern’s parents were thrilled that their daughter had found a boy who wasn’t covered in tattoos or wore back eye-liner like the pictures of the boys on her bedroom wall, pictures her parents tore down and forbid to ever be put up again. Shell’s sisters, Petunia and Lilly both married Citadel graduates and lived in large upper class homes on the Vineyard. Their husbands were extensions of their father, High Tea Unitarians who became tax attorneys, who joined the Athenaeum, who returned home to manage family investments over shots of brandy in soft leather high-backed chairs in country clubs and men’s salons, buried in the Berkshires, far away from prying eyes. The flagged husbands of these two flowered sisters provided ample opportunity for society and social, a respectable blending between the proud Mayflower inheritance they had all been raised with and the old money of the Old South, a coming together of two worlds, like bastard children of Lee and Grant. The women were thus left to their own world of Boston society, their own private organizations and gatherings of respectable ladies and mercy-granting fundraising event aficionados, organizing the further proper education of further proper children, to cultivate all things proper and further. Shell spent many years like a servant to these conventions, to this lifestyle, locked away in the family homestead, only escaping to be baptized through the private school and private tutor and private piano and French lessons, the privation of her own soul, her own passions, her own life. Growing up alone in her peach-colored dollhouse of a bedroom, listening to the niceties and politeness of her sisters and her mother and her aunts, through the old pine floorboards, watching her father and her brother-in-laws pass in and out in the night like Vampires, she went to the events, to the Church, to the schools, and wished they were all, somehow, better sooner than later, dead. If it were not for Granny Moons, she would not have made it this far, age sixteen, and her first boyfriend, and her first chance to share the private world that only an old Oak tree shared with her, with another person.

It wasn’t that Shell wished her family harm, or herself, or anyone for that matter, but that for some reason beyond her, for as long as she could recall, she despised the way they said one thing and meant another, which meant, she despised their life. The Northern Niceties, as some call it, claiming a liberal ideal and theology but jagged guarding a conservative cynicism and sinister streak, the most two-faced of sins, praying to a Universal God and claiming the Dignity of all people o Sunday, hoarding money and for themselves and then hoarding themselves into small and tighter and more finite spaces where the great unclean masses could never proceed. For some reason, one of her “gifts” Shell referred to it as, she was neither happy nor sold on their life. Any mention of conformity into this life and society raised within her a storm of anger and resentment. She thought that people should mean what they say and if they cannot mean what they say, they should try to find out what it is they really mean. Granny Moons was always very honest with Shell, that’s why they had a been friends since she was a child.

Shell’s parents always knew their daughter was different. She was born a sickly white-skinned and underweight child, emerging from her mother’s well-tailored womb with a large black mole on her left cheek, a mark that no one else in the family shared. Her parents named her Shell as in “seashell,” because she was so pale and delicate, different from her sisters, the mark on her cheek looking like a small hole in the middle of fragile seashell, something old and worn down over time, what the old Puritans used to call, a Witches’ Shell.

In the crib and once on her feet, with or away from the au pairs, she kept to herself, an unusually quiet baby who occupied her childhood alone in her room with invisible friends, old women, nurses, who resisted the flashcards and attempts to bring her up to speed to enter a competitive Kindergarten, instead gazing off into the distance as if she were looking at some great astronomical event, or perhaps watching someone sneak into the house, steal something precious, and stealth away. They tried to socialize her at birthday parties with local well to dos, but it was no use, she would wander away from the kids and begin having a conversation with a flower bush, or a squirrel in a tree, or more often than not, the tree itself. She said she preferred the company of her invisible friends more than the local children her mother arranged for her to merge with, her favorite invisible friend of course, being, Granny Moons.

“Granny Moons told me that the Indians once believed the Trees could talk”, she said to her mother when she was barely six years old.

Her mother replied, “Isn’t that nice,” and pretended like she actually meant it. Her mother would say to company when Shell mentioned information gleaned from her imaginary conversations, Shell has invisible friends these days, and her mother’s company would reply, Oh, that’s nice, My Beatrice did as well, she’ll grow out of it someday, they all do, and her mother would say, Yes, they do.

Eventually growing a quick wit her mother often predicated as overly sensitive, to evening conversation, Shell found herself from age twelve onward to taking to her own room, her own space, if not her bedroom for solace. As her parents did not respect the autonomy of Shell’s room as Shell’s domain, she took to taking long walks and to time alone at the Bull Street Branch public library, which her family found absolutely repugnant. At the library, which took her a considerable amount of time to get to, Shell discovered all sorts of people that she had not encountered previously except on the rare TV show or movie that her parents allowed her to see. She gazed in fascination at people who dressed differently and spoke differently and acted differently than the society in which her family raised her. The librarians recommended she read lovely books with lots of fine pictures, but Shell quickly grew bored with such books and wanted to know what the adults were reading.

One day, she got caught by a strange site, a group of all black-wearing city kids with dyed black hair and black fingernails and lots of make-up like Halloween were sitting at a table together in the back of the library. Being that it was seven months until Halloween, Shell pretended she was looking for books in the stacks but listened into their conversation. She didn’t understand much of what they were saying other then one kept talking on and on about some books by some writer named after a tree, Hawthorne. After an hour of being closely watched and prayed at by the librarian, the kids left the library, leaving behind a pile of books on the table. These books became the key to her early awakening; Shell spent her days and early evenings after private school, buried in books on Vampires, Ghosts, and Witches. When one of these books, A Southern Compendium of Paranormal Stories was left on the sitting room table and commented upon by one of her mother’s society friends, her family officially became concerned for the unfamiliar distemper of their youngest child. Neither believing in phases or periods or moods, for such things are the excuses of the lowly born, among their kind, the family began to attempt to isolate their daughter from the library, enrolled her manners classes, which had the reverse effect upon her independent fortitude.

Shell’s interest in books of such matter led to her developing an overly attentive nature to things which polite company do not talk about. At a social one Spring evening, Shell shocked and stunned all those within earshot of her with tales of haunted plantations and old curses still as fresh today as they were a hundred years ago. And when the widow found out her nephew had stolen her inheritance she cursed him to haunt the fields for the rest of his existence! She shouted with enthusiasm. Her parents were humiliated by the passion with which their daughter could speak about such things for seemingly hours at a time. When her mother would try to politely end her daughter’s storytelling with the proper, Aint that something or the Well then, Shell would look at her mother in disgust and reply, Mother, don’t try to pass me off now, to which her mother would reply, Hush now, Shell or find a more decent subject for proper conversation. After a while Shell drew tighter into herself, and extended her walks into the locations that her books most often referred to, especially Bonaventure Cemetery.

It was in Bonaventure Cemetery where Shell’s awakening continued. The statues of fallen angels, the graves decaying and aging before her eyes, the moss covered oaks, the hiding spots and the places where she could be alone with her books beneath something terribly beautiful, gave her a sense of independence from the world she so seriously felt she was not a part of. And yet, that world followed her inside the cemetery, The tourists in their vacation wear, the locals out for a historical daytrip, fledgling artists and photographers, the occasional descended family or old widow coming for respects, all invaded her world, She could easily mock and took great privilege in doing so each of these visitors. Among these people, people like her family and the kind of people her family politely tolerated but treated with a gentle outsider’s gaze, she was free to stare at them, hate them even, but blend in and out of them, like a ghost that only went noticed if you were looking carefully at what was not right within the picture. With her neatly cut blonde hair and thin, misshapen frame, dressed in the only clothes her parents would purchase for her, proper dresses and open-toed shoes, feeling awkward and uneven in her mother’s old fashioned and out of date imaginings, Shell wandered in and out amongst the visitors as if she were both one of them and also some sort of tourism subject of appreciation. When her mother and sisters asked her where she was spending all her time on the weekends and she replied, visiting the historical sights of our city, they assumed she was finding her way into Savannah, though respectably so, and that her active imagination would eventually blend into the natural course of things. There was hope for Shell yet. They did not know that she fancied friends far outside their world.

First off, Shell found herself increasingly fancying the occasional wanderer or small group of wanderers, dressed head-to-toe from black, wearing symbols of some strange shape, one she recognized as an Egyptian thing with a loop on top of a cross. The black wanderers, weirdoes, her mother called them when they occasionally drove by one, the librarians insulted them as once they left the library, didn’t look like her sisters, certainly they were no flowers. More so, they didn’t seem to mind at all the scowls, frowns, and unpleasant looks that passers by regarded them with. Alone at night, in her overly-pleasant room, with her canopy bed, fine oak furnishings, and framed pictures of family alongside hung images of horses in their best pre-derby postures, which her mother thought would make the room a bit more special, Shell imagined herself one of these black-dressed wanderers, smoking their smelly cigarettes, listening to their spooky music from their portable cassette players, talking about literature, the paranormal, and death like she often spied them talking about. Shell painted her toenails black and did her best to conceal it from her family. Removing the black from her toes when she knew her feet would be exposed always felt to her like she was erasing some part of herself for the moment.

Her second friend was a large Spanish Moss-covered tree in the far end of the cemetery, in a corner that seemed to be missed by most of the visitors, socials, and wanderers. She found this tree the first time she had decided to run away at the age of thirteen, running straight to the cemetery after sneaking out her parents immense home, Shell wandered the cemetery in the dark for hours unsure of what to do next, until exhausted, she sat beneath a large tree and exhausted, fell asleep. That night inspired by her books, she thought, Shell dreamt of a large old Witch, with huge hands, cradling her in her arms, and holding her safe and secure. In the morning when she awoke, she decided to return home, her parents had noticed her missing and were waiting at the house with the police. Her family, the police, and their minister declared the running away to be based upon demonic forces, and her family soon forbid her to be reading books from the library without their permission. It took nearly six months for her parents to begin to think everything was going to be fine with their daughter until Shell became more cautious of how to sneak books past her family. She put covers on her paranormal books so as not to draw attention, dust jackets from the library of more respectable books, and sat for hours at a time, eventually into the evening hours, looking all high literary but really sinking deeply into a world that was so alien to her parenting. Shell also started returning to the cemetery, and the Tree she spent her first independent night under. As Shell grew, her friendship with the Tree grew as well, the two of them concealed as one. Granny Moons, she named the Tree.

Eventually, by the time her beauty was blossoming and her purity was a silent concern amongst the murmurs in the home, as her parents began to realize that their daughter had interests in reading and adventure which they seemed unable to control, the idea of her spending so much time around unclean things compelled Shell’s father to arrange for her permission to visit the library at Southern Baptist True Faith Seminary, which he was a Trustee on the board of, and to read and study there as she saw fit. The family figured that maybe they could encourage her literary enthusiasm but in a proper direction. Although her mother abhorred the idea of her daughter becoming some sort of intellectual, a thing she feared for her daughters almost as much as she feared them being lured into the craze of dating colored boys that seemed to be coming into style amongst the Godless Catholic girls of the North as of late, she prayed that the locality to good, God-fearing young men and the proud Southern Baptist tradition, would provide a swift sense of completion to the wistful longing her daughter had taken to as of late and those horrible books she had taken to read. She believed her daughter to be safe with these boys and although they weren’t Citadel material, perhaps the exposure to the Seminary would inspire Shell to appreciate all that her family had to offer.

Shell become a regular around the Seminary, a staple of the library environment after two years. Occasionally she helped the staff carry boxes in and out of the buildings or help set up for new student’s day. The students referred her as the rich girl who read behind piles of books, by the staff as Mr. Southern’s awkward daughter, and to a few students who actually spoke to her, the strange girl who was always sneering at people while they spoke the word. There were a few rumblings that she had been seen with books of questionable nature, but none of the student’s would ever say anything directly to her because of the position her father held at the Seminary.

As for her observations of the seminarians, Shell found watching the Seminary boys stumble over themselves at the few women there to be funny, a few even blushed when she would stare at them using her southern fascination to reach deeply into their chest. One seminarian, Vern Layson, a short brown-haired and brown-rimmed glasses wearing boy with a strong West Virginia accent in his late twenties, would look at her, blush, and then fumble awkwardly for a Bible he kept inside his jacket, before striding away, deeply searching for some passage or psalm that he seemingly needed to pray over her.

She thought the high and mighty attitude of some of the Seminarians to be unflattering at best, and often strutted around the campus with a sense of superiority that revealed her fine heritage but her feelings of being special amongst people who were anything but special; they all wanted to be just like each other. This assimilation of personhood, as she heard one black-dressed person refer to a group of local officials with, only inspired her to investigate the gnawing inside of her more for what was not considered proper for a girl of her standing. She secretly read books at the library on coming of age, on developing sexually as a young woman—for such things were not discussed in polite company–, even finding a stash of her father’s filthy magazine’s one day in his billiards room, which she was forbidden to enter as no place for a young lady to be, and sneaking back constantly to investigate and figure out the pictures and stories within. In one of the books on Witchcraft she found at a mall bookstore, she read about, the Great Rite, the awakening to womanhood through a ritualized, sexual act, as she understood it. At this point, her mind began to explore the idea of the relationship between her interests in the paranormal and this strange needing inside of her.

While her mother pushed manners and etiquette, on being a proper young lady, and had great hopes for eventual presentation to decent society, Shell began to feel an inclination toward that which demanded attentiveness inside of her. She had not lost her interest in late night wanderings either and outside of her escapes to Granny Moons and the cemetery, her growing fascination with the Seminary boys, and her continued secretive investigation of the paranormal, she had taken to long walks around the Seminary, especially the old white antebellum building that adorned the seemingly haunted grounds.

Shell’s first kiss came when she was barely sixteen in the prayer room beneath the old chapel. She had been wandering through the dark hallways after hours when she walked right into Vern Layson who had just emerged from one of the study rooms after working on his next’s days sermon for hours. When he told her that she should be careful from wandering the campus alone at night lest people begin to wonder about where she was off to, she replied that, aint me that people should be concerned with, its you being around someone like me, that should be your concern. When he replied that, and what about someone like you should I be concerned about being seen around? She stepped into his space, and touching her finger to her mouth like she had seen one of the black-dressed women do, she replied defiantly, A Witch. Vern began to reach into his jacket, mumbling, then paused and said, We got Witches in the Appalachian’s, where I’m from. They aint no good, gotta be ministered to with word. A person like you shouldn’t joke about something like that. Shell smiled, looked him up and down, paddled her way through her first seduction, maybe you underestimate the weird girl behind the pile of books.

From that point forward, from Vern’s, My God, what am I doing? to his immediate apologizing as he began to kiss her, to their eventual Friday night meetings alone in the chapel, where Vern tried to minister to her but quickly found himself interlocked with her in the darkness, kissing and fondling each other, he knew he had to take her very seriously. He felt that Shell represented some sort of test, someone so young and innocent who made him feel, so close to the LORD because of how far away she was. Maybe he should try and save this one? He questioned himself as he spent the nights awake after their secret encounters turning his heart against his conscious. Eventually, he decided that he had to do the proper thing with Shell and be respectable to his calling, like he did at home before he arrived at Seminary. As for Shell, she quickly realized her decency was the one thing that proper society so admired worthy of protection, and yet, so hungered to feed upon.

By the late November she asked Vern if he wanted to meet her Granny Moons, and figuring that he was going to meet some old southern granny, figured that it would give him a chance to understand better the sweet child who was rapidly questioning why he had traveled so far from home to go to Seminary, who made him question his own reasons, which only further strengthened his calling in regard to Shell and the LORD. She arranged to take him on a Friday night and he did all his weekend’s work in advance to keep the time open.

An unseasonably warm, and full mooned sky greeted the Friday of their meeting. When Vern arrived at her parent’s large, old plantation home he felt further from where he had come from then he had his entire life. In his old 1973 Ford Wagon, the last thing he took from his father, Vern wondered what his parents would have thought of the idea of their little boy, raised in a trailer in the mountains on Blue Grass and the Bible, driving up to a house like this. Shell greeted him at the door and introduced Vern to her parents without giving either her parents or Vern warning that such a meeting would take place. Vern only knew that her parents were stuffy, old fashioned southerners who had somehow missed the transformation of southern roles during the early 1970’s, something Vern was against as well, and who did not understand her nor respect her right to be who she wanted to be. As for her parents, when Mr. Southern enquired into Vern through the Seminary Dean of Students, for Mr. Southern had the staff keep an eye on his troubled daughter, Vern came highly recommended from the Seminary professors as a person with an honorable reputation though humble beginnings.

With this surprise meeting, Shell’s parents quickly tucked into their manners and welcomed Vern into the home. He was dressed in brown corduroy pants, and an off-white button down shirt that seemed more off-white from lack of washing then to its actual color. A large brown thrift store dress coat seemed to hang, rather largely, over his medium frame. He presented himself as polite and friendly, gave Shell’s dad a firm handshake to Mr. Southern’s astonishment of the seemingly mild country boy. Shell showed off her little Appalachian minister with the sort of glee that someone shows off Mohawk, a sort of unsteady defiant attempt at self-identification. It wasn’t that she wanted her parents to hate Vern, she was slowly starting to warm up to him herself, but she wanted her parents to see that she was growing in her own ways and was going to be who she wanted despite what they thought her to be. Vern bowed in the presence of Shell’s mother, he seemed overly eager to impress his manners she thought, but was still happy that her daughter’s first stray home was indeed one who understood the concept of manners and proper behavior.

The rest of their brief encounter enfolded like a repetition of an old play to Shell’s ears, just with a different lead actor. Shell’s parents, gently and cautiously poking into what little information they had on their daughter’s current interest, and though he stood tall and straight, Vern found himself treated with an unpleasant probing of, So, Shell says your people are from West Virginia, coal country? To which Vern replied, Yes, my family had been coal miners back as far as we go, accept my Pa, he was a mountain minister, how he met my mother, to which Shell’s mother replied, Well, good for you. Mr. Southern offered Vern a seat, which he politely turned down, before asking what Vern’s mother did for a living, if she cared for the home or worked about, to which Vern replied, she aint with the world no more. The Southerns immediately apologized and offered their best condolences of, poor child, our prayers are with you, to which Vern replied, it’s okay, she was a Pow-wow woman, and it’s better for her now where she is. Shell’s parents nodded kindly, but looked at each other trying to figure out what they just heard. All Shell’s mother could muster was a sincere, Well, that’s how life works sometimes dear, it’s all in God’s hands. Vern shook his head to affirm, Indeed, ma’am.

They offered the two of them some sweet tea, but Shell said they had to rush out before they were late and swept Vern out the door while he extended his good graces. Her parents, dreading that their daughter was in the company of such a person as Vern, but feeling safe that Vern was probably incapable of figuring out basic female anatomy told Shell to be home by eleven and Vern to drive carefully with their delicate treasure.

Vern had been sworn to keep their destination for the night a secret, telling her parents they were going to see a chamber music performance, he was indeed surprised when they rolled up a block away from the cemetery. Sneaking in through a hole in the Western side of fencing. It’s bad luck to go into a cemetery at night, Vern said, back home, everyone knows you don’t go into a graveyard at night. He said, stopping by the opening of the fence. Bad luck for whom? Shell replied. For anyone dumb enough to go where they can’t be rescued or seen from the powers of darkness, Vern replied flustered. Aint no powers of darkness back here, Vern, just dead people. Besides, don’t you want to meet my best friend in the whole world? She said, her hands on her hips, and coyly smiling at Vern. You’re best friend is waiting in the cemetery to meet us? He asked. Besides, I though we were gonna go meet your Granny Moons. He said confused. We are! She lives here! Shell replied. She lives in a cemetery? Shell nodded in acknowledgement and then quickly slipped under the opening in the fencing. I thought your people were old southern money, Shell. He called out to her. Come on Vern, don’t be such a dud. Her voice said as she vanished into the darkness. Dear Jesus, give me strength, he said as he ducked under the fencing and his hands were met by Shell’s.

Shell pulled Vern along through the labyrinth of crypts and grieving angels, he kept looking at his feet so as not to trip over any of the graves or immense roots jutting out of the earth in the dark. All that Vern could make out in the growing all black night was the occasional flash of Shell’s eyes, mischievous and yet still so innocent, sincere, as if she were racing toward adulthood faster than he was racing toward the LORD

Suddenly they came to a halt. Shell kissed him deeply on the lips. He breathed her air fully into his lungs. Shell said, hold on, I’ll get a light, and Vern heard the sound of Shell searching through her purse, and then a click, as she snapped a lighter on and lit three tea light candles, placing them on the ground. With each candle she lit, he saw for the first time, that despite being so strange and talking about such strange things, that she might just be a lost sheep in the world, not one of the black sheep like he had come to consider her as over the last three months. Vern paused for a second, a smile crossed his face, as Shell seemed to stop and pose, her feet together, her arms gently extended to the sides in presentation of her secret world: in her blue and white casual dress, she looked like a statue of the Virgin Mary. This one could save me (or, this one could be saved still), he thought to himself.

Meet, Granny Moons! Shell said in excitement. Where? Vern replied, confused and feeling slightly fooled. There was a rumbling in the distance, as if someone or someone’s walked nearby, but Vern couldn’t make out from where, although he did notice Shell look in the direction of the sound, then shrug it off when it stopped, return a smile to Vern. Here! She said, this tree, this is Granny Moons! He placed his hands on his hips and paused for a few seconds. You’re granny is a tree? Another snap in the distance, a crunch, Shell half-acknowledged the sound, Vern looked again in the direction. Stray dog, they wander through now and then, she said before adding, you look so disappointed, isn’t she great? Vern flopped to the ground. I guess I should have expected this from you. Vern reached inside his jacket.

Oh, Vern. No, No, don’t start preaching from that book now, referring to the bible that Vern always carried with him. This is important to me; you’re the first person I ever brought here. His hand paused in his jacket, seemed to replace the good book into its hiding place. When I was younger, I ran away one night and ended up falling asleep under this tree. She watched out for me that night, we became best friends afterwards.

Vern looked up at the tree. Between the full moon in the sky and the light shed by the tea lights he thought the tree looked like a hobbled old woman with a hood and a cloak, the branches, elongated fingers seemingly reaching out and sheltering the immense, round-patterned roots, like two hands over a cauldron. Vern shivered. It looks like a Witch! He said angrily. That’s exactly what I thought the first time as well! Shell shouted with excitement. A slight wind blew, it almost sounded like a rustling mixed with a murmured laugh. Shell felt safe, more so, like herself, beneath the long arms of the Witch, here with her little minister.

You brought me to see a tree, which you think is your best friend, because it looks like a Witch? Is that what you’re telling me Shell? Vern said in a voice that felt to Shell like he was questioning her sanity.

You know Vern, I read in my books that sometimes when kids are young and they see invisible friends, that they are actually seeing ghosts from the past, and that as you get older you lose your ability to see ghosts and things like that. When I was young and my mom was angry at me all the time for not being the sort of southern society mop and bucket she wanted me to be, as a child, my God Vern—Don’t take the Lord’s name in vain, Shell, Vern hotly inserted—as a child, she continued, I had this invisible friend, this old woman, like a Witch, she had the best stories, Vern. I felt like I was someone then, like I mattered enough that someone watched out over me and treated me with care and attention. Vern rolled his eyes at her. Shell continued, When I found this tree, when I dreamt that night of a Witch while I slept on her, she reminded me of my invisible friend from when I was younger, she replied in a hurried manner. That don’t sound right to my ears, Shell. Not right at ‘all.

Shell leaned back against the tree, against the large bosom-like stumps of some long-lost branches. Not you too. Vern shot up straight, turned to face her. What, Shell? You want me to accept that you come here, to a cemetery, in the dark, and spend your time sleeping on a tree because it reminds you of a Witch. Does that sound right to you? Shell’s face was downcast slightly, it’s safer here then anywhere else I know, she said. Safe? What makes you so sure of that? He said seriously, somewhat coldly, posing the question. Oh, the Old Witch watches out for me, Shell replied her voice reflecting a darker tone to it. Witch? That’s Devil talking. Vern replied. Aint no devil here, but you and I, Vern.

With that, Shell walked up to Vern, put her hands on the edges of his jacket. He resisted slightly, protecting the bible in his coat pocket, and slightly pulled off his jacket, closed it at the front, dropping it neatly to the ground, as Shells, hands searched his chest, their mouths connected, No, Shell, I need to be stronger than this, he said between kisses. Shell gently guided him to the ground, Hush there now my little mountain Minister. Let this Witch take care of you now. She crawled on top of him, looped her arms through the straps on her dress, and revealed her small, perky breasts, then guided Vern’s hands to them. My God, my God, not you, Shell, not you. Vern said, shaking, nearly stuttering.

As Vern lay down beneath the long arms of Granny Moons, as Shell explored him like a subject of study and curiosity, the same way she explored books on the paranormal and watched strange people pass in and out of her world, his hands shaking, his face filled with regret overcome by wanting, Shell urged him onward. The massive old tree, Shell’s reeling head, as she attempted to straddle him, confused, not knowing fully how the whole procedure actually fit, worked, seemed to become one, Shell and the tree, in Vern’s eye’s became one, old crone and young maiden, the same person, one Witch from two wicked creatures, throbbing and robbing down on him.

Fumbling for his belt and zipper, with one hand, and reaching out to his jacket with the other, fighting two distinct impulses, one for the LORD and the other for Shell, he thought himself bewitched, on the verge of losing his calling, nearly damned. Come on, Vern, give it to me, awaken me, this is what I’ve been waiting for, reading about, and I chose you to take me through this passage, what’s wrong with you, I thought you wanted this too? She said, still moving across him, allowing him to turn to his side, as she began to move to her back, thinking he would take the opportunity now that she had brought him to an apparent rise. Shell! Shell, he screamed, muttered a biblical passage, as Shell just removed his little minister from his pants and Vern’s unexpected arrival, with her first firm touch, blasted across her dress and hands. Shell fell back, her head against the ground. A small gathering of four black-dressed Goth kids, still remain hidden behind a crypt nearby, fighting their giggles, taken in by the scene of youth seeking confrontation with darkness.

Shell lay still, unconcerned for her dress which she wiped her hands on, fighting back a tear in her eye. Shell…. Vern started before she interrupted him, It’s okay, Vern, I read it aint easy for a man the first, I know your feelings are for me are genuine and good, it’s okay Vern, next time. Vern had his jacket in his hands. His pants were still undone. He fumbled inside the jacket hurriedly, looking for redemption.

She smiled up at her mountain minister seemingly trying to redeem his decency with the good book. For the first time, she admired she realized she admired his connection to what he knew himself to be, like she knew herself to be, and she playfully asked him, Vern, honey, what was that Bible verse you said as your business arrived? Right then she felt a sharp, breaching pain in her lower abdomen. Vern hadn’t penetrated her, not even close, had only one time felt inside of her before. She thought to herself that it shouldn’t hurt yet. She had read that sex hurt the first few time for women, she expected the pain to be blissful, but not like this, this sharp pain, and then again, and again, just in different locations, all around her abdomen. She looked at Vern who was now sitting astride her, his eyes forgiving and kind, like he had just baptized a child. Exodus 18:22. Shell. Thou shalt not suffer a Witch to live. Shell’s eyes moved from Vern, to Granny Moons, climbing her body, slowly, from inside the cauldron, to up her legs and breasts, nestled in her arms, her wild-moss hair cradling around her, as she awoke to the starry night, to oblivion, in the arms of the Old Witch.

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.