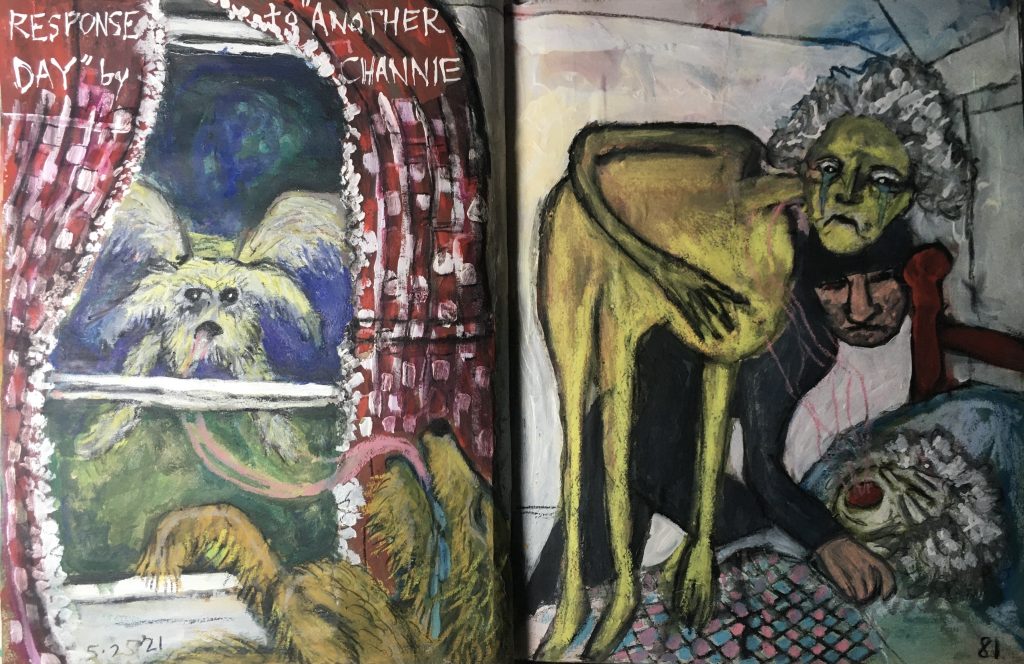

Erika Cleveland

“Your Dog was Dead.

You, Likewise, Were Almost Dead.”

Response

Another Day

By Channie Greenberg

Inspiration piece

Minute upon minute, the days creep. It is not so much that looking out my window occupies me or that counting the cracks in my ceiling is wearisome as it is that sighing has become tedious.

More exactly, neither my cuckoo clock nor the mirror in my main hall resounds akin to the once rushing footfall of my elderly dog. That beast would lick my cheek, or, in the least, would sit on my feet while I used my keyboard.

“Bed,” to that critter, was wherever I was stationed. If I fell asleep on my window seat or on the toilet, Old Max would stand guard. If he drifted to sleep, the slightest change in my posture would rouse him to his sentry duties.

Whether I was robed in a housecoat or a fancy dress, that canine would look upon me with admiration. I could be surly. I could be grim. No matter: he’d make sure that I was never abandoned by him.

Anyway, on a day devoid of sunshine, when merely a handful of flowers had dared to bloom beneath my windowsill and when the birds sang angrily, only the newly hatched cicadas announced that they were thrilled with life. Timothy chose that point on my calendar to come calling.

Old Max had barked when Timothy had repeatedly dropped the front door’s knocker before letting himself in. Growling, my dog ran down the stairs, toward my home’s entrance.

“Madame,” Timothy had intoned as he presented me with a parcel. “I believe this was delivered for you.”

I stared at the sack containing beans, eggs, sausages, and mushrooms. That breakfast almost smelled good. “Thank-you for porting. Just lay it on the sideboard, please.”

“It will spoil.”

“That’s of no matter to you.” I arched an eyebrow at Timothy, hoping for a stout affect.

Instead, that square-jawed man shrugged and placed his bumbershoot in an appropriate receptacle. Rain was boorish. Foul weather, in general, was boorish. Sir Timothy was the most boorish of all elements.

“Dear One, it has been so long since I laid eyes on you.”

It had been exactly three days.

“I beg you, please join me for a stroll.”

The man was daft, truly, entirely preposterous. I liked my room. I liked the home in which it was located. I liked my dog.

I did not like inclement weather. I did not like Timothy. In fact, it could be said that I despised him.

“Your breakfast is losing its heat.”

“Yes.” If only the same could be said about that man. With every word, he looked at me in a seemingly increasingly licentious manner. I was no pious vestal, but I did and still do despise men who assume that good looks and kind gestures will warrant them to draw closer. Besides, he had not cooked my breakfast, but had merely picked up what the delivery service had left on my stoop.

The rain within cast dark skies that were opaquer than the rain without. It was all I could do to feed Old Max and to take no notice of my visitor.

“Then I shall eat it.”

“Then you shall.”

Unfortunately, Sir Timothy failed to leave after taking possession of my breakfast. Rather, he made himself comfortable in my dining room.

I shrugged, walked into my kitchen, filled Old Max’s bowl, and took a somewhat stale pastry to the table.

Timothy continued to stuff spoonfuls of marmalade onto toast. The service had been thorough in its meal preparation.

“I thought you had a cook.”

“Indeed. A maid, a butler, a liveryman, and a gardener, too. None, however, are pleasant companions, unlike you.”

I harrumphed, shoved the rest of the pastry into my maw, and gestured for Old Max to follow me. “Let yourself out when you finish. Also, please tuck all of your waste papers into the bin.”

“My lady?”

“…is retiring. Good day, sir.” It seemed like hours, albeit it was only twenty minutes, before Sir Timothy shut the front door behind him. I watched from my window to make sure that he had left. Thereafter, I descended the stairs and threw the bolt across the door. It would be better to eat the bits and scraps left in my kitchen than to chance another encounter with that man.

Be that what it may, hours later, the knocker sounded again on my front door. For reasons known only to fey and demons, I screamed and continued to scream until the knocking stopped.

Old Max howled in response to my shrieks. It was of no surprise that the birds in my yard stopped chorusing.

Sometime later, I fell asleep on top of my duvet. Old Max lay curled at my feet.

I awoke, however, in a hospital ward, strapped to a bedframe. One of my wrists was enveloped by a cloth bandage.

The other residents of the ward were either laughing manically or crying shrilly. None of the women in that room seemed to understand the utility of silence.

After too much time had passed, a uniformed nurse, all starched apron and attitude, approached me with a tray of pharmaceuticals.

“What?” I muttered.

“Your brother thought it best.”

“Timothy?”

“Yes. He signed all the necessary papers.”

“That blackheart! That quisling! Eating my breakfast and making eyes wasn’t enough.”

“Dr. Norton will inform you of her assessment. Meanwhile, Lambie, please take your medicine.”

I would have hit the tray from beneath and watched its various pills and potions fly had I not been encumbered by restraints. That good nurse, in the meantime, fed me one capsule after another. I don’t remember much after that.

That same day, or, perhaps, the next, a woman with bright yellow hair and wondrous blue eyes came to my bedside. She seemed impervious to the cacophony in the ward.

“Sara Utive?”

“Alive, not, apparently, well.”

“Your brother was worried about you. He found you unresponsive and your dog dead.”

“Falsehoods! That wazzock depends on my income to maintain his fancy life. No greater mingebag exists. What do you mean my dog is dead?”

“Respiration ceased. The veterinarian’s report indicated starvation. You, as well, almost passed on from lack of nutrition.”

“Balderdash! Restore my liberties this instant! I want to return to my home and my dog.”

“Your home has been listed for auction to pay for your stay here. You dog has died.”

“I’m leaving, instantly. What’s more, my home is paid for, is not in arrears, and Old Max licked my face just his morning.”

“You are a danger to yourself. Your brother was right in bringing you here.”

“I have no brother. Sir Timothy is as nothing to me.”

“I’m sorry. Perhaps, if you become more peaceful, we can release you from your fetters.”

“I will sue you and my ‘brother.’”

“You may do anything you please when you are of right mind.” Dr. Norton left.

In her place was the shepherdess to whom all patients were barnyard young.

A few days later, I was allowed to have my wrist belts loosened. A few days after that, my ankle bonds, too, were taken away. I was thankful to be able to use an actual toilet.

A long span of physical therapy, occupational therapy, group therapy, and individual therapy followed. Much later, I was permitted, under the supervision of a full-time care provider, to return home. I called Old Max.

My manager sighed and suggested that I take off my coat and scarf and seat myself in the dining room while she prepared our food.

I again called Max. There was no response. Could I really have been spelled? I sat at the dining room table. Cooking smells wafted in from the kitchen. As ever, I had no appetite.

On the table was an envelope addressed to me. It was from Timothy, who, it seemed was neither a knight nor a gentry of any sort. At least, his handwriting was legible.

“Dear Sara…” began the letter. I put it back in its envelope. Not only was there no response from Old Max, but there was neither the calming cry of my garden’s turtledoves nor the enchanting sound of its whinchats. The only noise that reached my ears was that of my attendant banging pots and pans in my kitchen.

I went upstairs, to my bedroom. It was musty; the window had remined closed for a long time. No Old Max waited there, either.

While upstairs, I changed into my favorite sweater set and skirt. Homecoming needed celebrating.

Downstairs, my place was set. A bowl, a cup, and a plate all were laden with attractive offerings. My keeper, though, was not in sight.

I peered out the front door, thinking, maybe, she had taken a smoking break. Only trees and flowers greeted me. The patio next to the side door, which was off of the kitchen, likewise, was unoccupied.

I sat down, again, and lifted a forkful of the scramble that she had made toward my face, but watched those bits tumble back to my plate. Similarly, I stirred the broth that my appointed guardian had left, but other than trying to force that liquid to go against the Coriolis effect, I left it alone. Just the tea called to me. I ought not to have sipped at it, though, given that I felt compelled to sleep after it was finished.

I woke up to Timothy’s face. It had lost its lecherous quality. He had pulled a chair near the sofa upon which I had slept. I glanced from the sofa to the ding room table. The bowl and the plate had been emptied, but not returned to the kitchen.

“Did you shoot my dog?”

“No, he was dead. You, likewise, were almost dead.”

I propped myself up and gazed at my shoes. It was a pity I had fallen asleep in them. Probably, my sofa was soiled. I next gazed at my wrist. There was a pucker where a fresh scar had formed.

“Did you read my letter? I am very unhappy that St. Martin’s was the only address.”

“You’re no ace. From this time forth, if I go to pot, leave me be.”

A tear dripped off of my brother’s non-aquiline nose. He blinked as more water filled his eyes. “You’re all I have.”

“You mean, I’m all that’s between you and the debt collectors.”

“Not true!”

“You tried to sell my house.”

“The hospital bills were outrageous. A salary advance, though, solved that problem. Notice that we’re in your home?”

“Where’s Old Max?”

“Dead.”

“Where’s Old Max?”

“I wanted to hire a private nurse, but you fire all of the employees I engage.”

“Like the newest warden?”

“She’s also lost?”

“I suppose. No loss; her cooking was appalling.”

“It’s been a long time since you voluntarily tasted food. Wait! I thought the hospital had helped you.”

“No. They helped themselves. They ate up my money. I ate up very little. End of story. Dr. Norton drives a fancy care. The head of the Nursing Department like gemstone rings. It’s a pity that you paid them. Why not just let me fade and then inherit my ‘fortune?’”

“You’re my family. If I could, I would restore you to health. You used to be vivacious, fun to be with. I don’t need your money. I have a good job.”

“Old Max used to be alive.”

“Regrettably, Richard Taylor also used to be alive.”

“?”

“Dr. Norton said you might never remember. That man. No, that depraved, vile, corrupt, pernicious lout…”

“You’re none too fond of him.”

“Sara, he raped you.”

For years, I had long wondered about the scars on my legs and had written them off as residuals from my having tried, somewhere, at some time, to climb through brambles.

“So why hospitalize me? You’re supposed to be a gallant. Why not hire the best lawyers or pay the police? For the right amount, they’ll perform unlawful acts.”

“It was horrific enough that you were hurt.” Timothy leaned forward me to hug me, but I shoved him away. I don’t like men (or women). He ought to know not to try touch.

“Sister!”

“Whatever. Please find Old Max and then return him to me. I miss him so very much.”

“After I ring up the agency and get you on a new minder. You’re not yet ready to be alone.”

“Whatever.”

My new minder’s name is Samantha. I bonded with her. After a few days in my home, she rolled up her sleeves and showed me the scars on her wrists.

She and I never discussed Richard Taylor. We say nothing of his forced intercourse with me nor of his death in a holding cell at the hands of other inmates. Instead, Samantha and I sit for hours listening to bird song. Sometimes, we take walks around the neighborhood.

Over time, I’ve learned to eat. I’m still underweight, but I can, now, put solid foodstuffs into my mouth, swallow them, and then keep them in my body. Under Samantha’s care, I’ve gained a stone.

Timothy doesn’t come around so much, anymore. He’s working full-time as well as has reenrolled in university for a graduate degree. He says that he’s begun to date, too.

I’ve accepted that Old Max died. I’ve accepted that I killed him from neglect. Still, most nights, I cry over him. Like me, he was an innocent. In his place is Petunia, a pit bull terrier with fawn and red markings.

Timothy says I should stop pretending that my furry companions are breeds of dogs forbidden by the Dangerous Dogs Act. Contrariwise, Dr. Norton, during a recent family consult, scolded my brother, suggesting to him that it doesn’t matter whether I own a “Bichon Frise” or a “Pit Bull.” After all, she thinks that Old Max was a “Papillon,” even though I knew him to be a Great Dane (my doctor’s still money-grubbing as well as delusional.)

——————————————————

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.