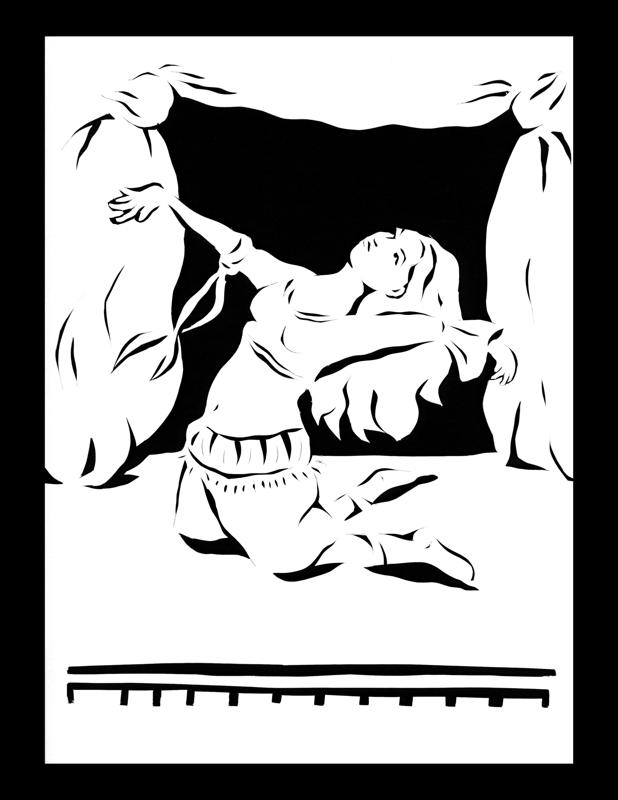

Lauren Silberman

Inspiration piece

Destiny

By Cheryl Somers Aubin

Response

She looks at the light trying to force its way into her room around the shades, strands of light like fingers, running over carpeting, on clothes to put away piled on the chair, an old magazine. Coming into the gray shadows, the dim, lifeless interior.

Katie turns over on the bed and pushes the comforter off in her first step to getting out of bed and trying to start the day.

She stares at the ceiling and for some reason thinks back to the assignment that came at the beginning of second grade. “Write down what you’d like to be when you grow up,” Miss Beebee had told her class.

She doesn’t remember if she looked at the other students’ papers, just that her list had five things on it and she had numbered the lines. First, actress. Second, stewardess. Then came ballerina, mother and bride.

Widow was not on the list.

She never did become an actress. Even though people tell her she is dramatic and funny, she wasn’t chosen for the 7th grade play to be part of the “nameless group” of people in the background. While she can’t remember the name of the play, as she pulls up this memory she’s surprised that she can still feel a bit jealous of Barbara Batterson, who starred in it. But a small smile comes to Katie, too, relieved to be feeling again.

She never became a stewardess, either, but remembers how thrilling it was when her neighbor took her up in his private plane and flew her over their neighborhood. Like stepping out into the blue sky she wasn’t scared, just thrilled and amazed to be up in the air, looking down. She was surprised that the air wasn’t blue, as she had always imagined it to be, but it still felt both magical and timeless as the wind lifted the plane and a wing lowered then righted. She wonders now why she became so frightened of heights as an adult. And why in her dreams these days she is always falling…

Katie never was a ballerina, either, but she did become a bride. For so long as a little girl she thought she could grow up and be a bride. As if it wasn’t a one day event, an ending and a beginning, but an occupation, something you could be forever.

And most importantly, she became a mother to two breathtaking girls. Motherhood deepened Katie in a way she found hard to express, but if being a bride was a day in her life, being a mother was her destiny.

Her two daughters were just a little over a year apart, the second daughter was a bit of a surprise, but a welcome one. She’s seven years old, “seven and a half” Amber would be quick to correct her mother. She’s got blond hair like her father but her mother’s dark brown eyes, and she mostly resembles Katie. She’s got a strong personality, too, and Katie wonders what her life will be like when this interesting, lovely child turns into a scary teenaged girl – with no father. Katie remembers when she was a teenager, how she herself had treated her own mother and thinks “what goes around comes around…”

Sitting now on the side of the bed, she clenches her fist, hangs her head as her eyes fill with more tears. What caused her husband’s death to “come around”? What could she have possibly done so horrible in her life that he would be taken from her and the girls? She recounts every transgression, every slight, every thoughtless word, every failure. Was it this? Was it that? What caused this to happen?

In reality she knows it was the icy road, the storm that came up suddenly. There were many accidents that night, just two of them fatal, both fathers on the way home to their families. She’d called and called his cell phone, but he had never answered, and she pressed the phone close as she heard his voice on the outgoing message, “Leave a message, I’ll get back to you…”

She was calling his phone again, when a knock came at the door at almost midnight. Looking out the window she saw the police car parked out front and somehow thought if she didn’t answer the door then she wouldn’t learn that her husband was dead. But the officer kept knocking until she did open it, and then spoke to her in a gentle a voice as her world collapsed.

Katie felt as if she had become a terrible mother. While she tried hard to reach for her daughters and help them, she was so depleted herself she felt she couldn’t really help them very much. She was frozen in her own soul-threatening pain. The sorrow coursed through her veins, cramped her muscles, paralyzed her breathing, like a heavy weight pressing down on her shoulders and chest.

Fortunately, there were sleep-overs at friends’ and dinners out with neighbors for the girls. Keeping busy to keep the pain away. Katie was often included, but mostly declined, taking every opportunity to escape to her room and her bed, the bed she and her husband had shared. She’d lie on her side and hug his pillow, escaping into restless sleep and away from her new reality.

After a few weeks, the girls went back to school and had gotten back into the routine of their lives. But when part of Katie’s routine was taking care of her husband, of being his wife, it was hard for her to find her footing. As time passed her emotions became all over the place. Coming home from school the girls might find that she’d not gotten out of bed, showered or dressed that day. The next day they’d come home to a spotless kitchen with her lying down on the floor cleaning the underside of the cabinets.

The day she went to drop off Amber’s mud covered coat at the cleaners, she was shocked to be handed her husband’s shirts she’d dropped off the morning of the accident. She didn’t know what to do. In a daze she paid for them and took them to her car. In the front seat she’d torn off the plastic, taken each one off the hanger, and held them to her chest. The tears flowing hard, soaking the shirts.

And as the invitations from friends finally came less frequently, their family, what was left of their family, started slowly to come back together.

She sees on the news that school are canceled because of a spring snow storm, and she lets her daughters sleep in. She takes a long, hot shower; the new shampoo smells good and she likes the feeling of the washcloth scrubbing her face. She puts on a dark green turtleneck, khaki pants and ties her hair into a ponytail. Finally she put a bit of perfume on her wrists.

Once the girls are up, all sleepy-eyed but smiling because there is no school, they all find the quietness of the snow comforting as they eat the pancakes Katie makes. The snow envelops their house and the three of them in soft cotton. The power has gone out and the only light coming through the windows now is a kind of soft grey, not depressing, but light filled.

After the breakfast dishes are cleaned, Katie gets out a pad of paper, tears two sheets off and gives one page and a pen to each of the girls sitting at the table with her. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” she asks them. “Think about it, write it down…”

Quickly Amber, writes down “Ballerina.” An easy answer as Katie looks over at her with her big smile on her face, and a pink tutu peeking up over the edge of the table. Katie had wanted badly to dance, too, to move her body gracefully. But she was awkward as a child and her posture was poor. Her body was not built to be a dancer. She suspected that Amber’s wasn’t either, but Katie would never destroy that dream. Amber had dressed that morning in her pink tights and pink leotard, too. She’d even put a crooked bow in her blond hair.

Amber dances away and Katie turns to see what her nine-year-old daughter is writing down.

Her other daughter, Jane, hated her name. She thought Amber’s name was so much more exotic, while the kids at school called her “Plain Jane.” Jane, the daughter who was most like her dad, was quieter and so hard to read. When Katie looked at Jane she felt a terrible homesickness for her husband.

Jane has a bit of blue magic marker on her arm. Katie looks at the multicolored stains on her fingers and knows she’d been up last night drawing. Jane hadn’t shared her pictures with her mother since her dad died, and Katie hoped Jane was able to process some of the terrible loss in her life through her drawings.

Jane had stared at the paper for a while, then in careful script she wrote number one, artist. Number two, diplomat. Her number three was writer, four a counselor. Katie is surprised and tries to hide her smile as she watches her daughter write down number five: Mother.

“I do, Mom,” Jane says, her voice cracking. “I want to be a mom like you.” Jane looks up at her mother through her too long bangs, her blue green eyes the exact color of her father’s. Their eyes well and then tears start falling for both of them. They sit quietly together and then Jane comes over and sits in her mother’s lap as they wrap their arms around each other. They stay like this for a while and then Jane returns to her chair.

Slowly she pulls off a sheet of paper and she writes “What I want to be now that I am grown up” at the top of it. She places the paper in front of her mom and gives Katie her pen. “Your turn now, Mom. It’s your turn.”

.

.

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.