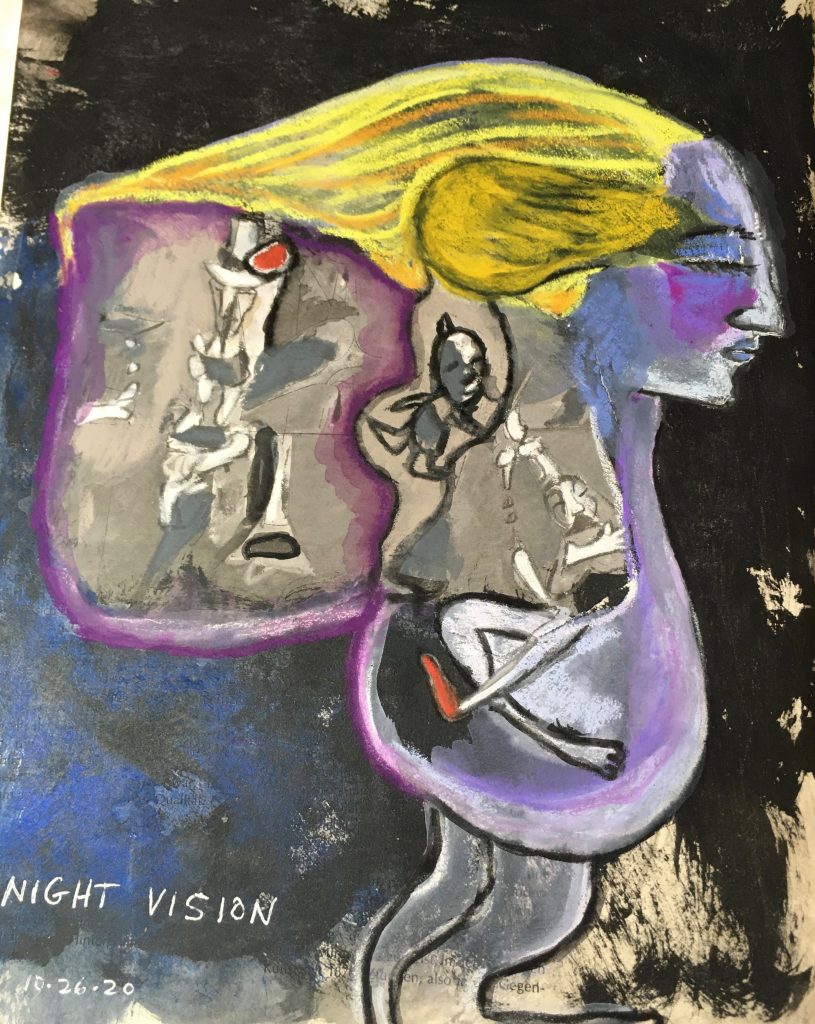

Erika Cleveland

“Night Vision”

Goauche and watercolor crayon in handmade book

Inspiration piece

Fecundity

By Channie Greenberg

Response

Amal, Carrie, Gertrude, Hilary, Joanne, Linda, Maribelle, Princess, and Suzanne became gravid at the same time. As they and their husbands were the sole participants in the Thursday Bridge and Cheddar Cheese on Crackers Club, the synchronicity of their expanded bellies was remarkable.

Initially, the fellowship’s members joked about “something weird in the water served alongside of the snackies.” They laughed, too, that Suzanne had gotten knocked up since she and Rudy were the club’s substitutes and as such were not always in attendance.

Subsequently, the men began to worry. Managing relocations and readjusting budgets were chief among their concerns. Not one among the bridge players was younger than sixty-five. All of them lived in Golden Days Retirement Community, a neighborhood that disallowed any residents under eighteen.

What’s more, whereas Rudy, Suzanne’s husband, and Thomas, Maribelle’s spouse, made a little pocket money consulting, respectively, on sustainability, and on human resources, the rest of the men, save for Lionel, relied on a combination of monthly social security checks and on their preprogrammed liquidations of stocks and bonds to get by.

Lionel had funds because he had been married before hitching to Carrie. His first wife, who had died decades earlier from ovarian cancer, had been the sole heiress to a rectal thermometer manufacturing empire, and had bequeathed all of her wealth to Lionel. It was rumored that Lionel and Carrie possessed enough moula to endow multiple chairs at Lionel’s alma mater as well as to provide an around-the-world tour for the entire Thursday Bridge and Cheddar Cheese on Crackers Club. Their actual fiduciary standing, though, remained a cypher seeing as Carrie wore clothing from Target and Kmart and Lionel drove a twelve year-old Honda Civic.

At the same time as their menfolk were fretting, the gals took action. They met doctors, avoided the media, sought new apartments, and shopped for layettes.

None of them had ever had children. Some of them had tried medical interventions. Others of them, who rejected excessive intercessions, had directly grieved their lost generations. Only Carrie, Lionel’s second wife, who was betrothed long after becoming perimenopausal, had never assumed that she might become a mom.

Regardless, fatigue, moodiness, and hunger sidetracked those gals from their assorted undertakings. They suffered the mental rust and nausea common to younger would-be moms, alongside of the heartburn, back aches, compromised knees, elevated blood pressure, and fatty liver disease more common to women their age.

Linda, the retired school teacher, and Gertrude, the retired chemistry professor, additionally, put up with constipation. The nipples of Hilary, the retired zookeeper, became uncomfortably sensitive and purple. Amal, the retired waitress endured a hairy belly. Carrie, the traditional housewife, and Princess, the former estate gardener, couldn’t stop burping and farting. Maribelle, the retired loan officer, and Suzanne, the retired meter maid, both squirmed from Bartholin’s Cysts. Only Joanne, the aerobics instructor, who still worked part-time, reported no special symptoms.

On their exclusive WhatsApp group, the ladies of the Thursday Bridge and Cheddar Cheese on Crackers Club debated the cause of their newfound status. Frequently, individual members had to excuse themselves from those chats to use the bathroom or to answer realtors’ calls.

Nonetheless, those gals rejected the possibility that they had shared an abrupt, profound hormone shift after collectively visiting the local zoo’s reptile house. Hilary had successfully persuaded them that their having stared at mating Komodo dragons could not have caused their common epigenetic shift.

The ladies similarly rebuffed the hypothesis that each and every one of them had been dallying outside of marriage. Only Antonio, Linda’s husband, was known to have prostrate issues. All of them, moreover, knew to avoid adultery. Most of the drugs available to combat STDs were incompatible with statins and beta blockers. The women might have wistfully giggled over the pool boy, the maintenance man, and the yard crew, but they limited their “trysts” to window shopping.

Amal offered a new conjecture. She suggested that the women had involuntary become medical guinea pigs. Weeks before she and her coterie had noticed their state of flowering, Amal had accidentally collided with a pharmacist. That pharmacist was walking through the locked hospital ward, where Amal’s sister was a nurse. Maybe, the drug doc had not meant to dispense medications, but to surreptitiously test a rare gonadotropin. Amal hadn’t thought it could be dangerous to her and her friends to deliver chicken salad sandwiches to her sibling.

The other gestating crones laughed Amal into silence. All the same, they provided no alternative theories in view of the fact that they were busy puking, shopping, and otherwise separating themselves from day-to-day life.

For instance, when not reshuffling the contents of her gut, Princess daydreamed about the fruit trees with which she used to work and about the orchids with which she used to fashion displays. She missed all kinds of blossoms and resented that she would have to continue to do so as Seymour had decided that they would rent half of his brother’s Bronx duplex. Their move-in date was two months away.

Linda, too, sidestepped reality to post, to Snapchat, pictures of her unrestrained belly and her pendulant breasts. Most often, her attempts got censored. Ever the feminist social sciences teacher, Linda insisted on celebrating pregnancy through “body positive” pictures. It seemed a pity that the social media insisted on showcasing the wonder of the female anatomy only in the case of young, lithe mothers-to-be.

Meanwhile, Gertrude seemed to have lost her mind when her nausea began coupling with paresthesia. She desperately wanted to return to her bench to find an easy cure for her woes and to determine why she and her buddies had become extremely elderly primagravitas in chorus. Yet, Gertrude lifted nary a test tube and centrifuged not one liquid into pools of differing densities; her professional sentiments only fired up when she was ill with low blood sugar around four most afternoons.

Suzanne, too, tripped the light fantastic to music only she heard. Accordingly, she urged her friends to improve the world’s status quo. She encouraged them, immediately, to: promote social ranking, purvey tertiary economies, convey norms, disseminate values, function as vehicles for the language of communal passions, and iconize popular ideals. Suzanne’s hormone swells gave her a loud voice.

In the interim, Zaccheus moved himself and his wife, Joanne, to a coop in New Haven. From afar, Joanne tried to continue her involvement with the other ladies, but those gals, who resented their inability to use facet time to quibble over Joanne’s opinions, barred her from their electronic clique. Those pregnant souls reassured themselves that it was okay to exclude her because Joanne was the prettiest, most symptom-free among them. The rounder they became, the more they relied on certain styles of logic.

Shortly thereafter, Maribelle determined that her peers needed to accept her heretofore hidden “ability” to engineer insights. Hourly, she pinged the other female bridge players to insist that they acknowledge her prowess with social architecture. She’d instant message them thrice daily, too, to warn them against all attempts to reify their former routines. Clinging to old ways was vexatious at best, unfeasible at worst, she cautioned. It would be better, she espoused, if, instead, they hoarded diapers and pacifiers. Likewise, her gal pals ought to cease trying to determine they destiny or its underlying causes.

Only fools believed pregnancy was synonymous with rejuvenation, she spouted. Her card playing sisters’ girth might be rising, but they remained a wrinkled, liver-spotted lot. More exactly, the study of human agronomy remained beyond their know-how; they should focus on basic concepts, like the nature of Kegels and of Braxton Hicks.

Wisdom aside, Maribelle’s expositions remained unpopular. That is, they went largely ignored until Hilary suddenly perished from a stroke. The women then texted each other that perhaps all issues associated with fecundity ought to be delegated to their doctors.

The ladies went this way and that way over Hilary’s death, but Jason was inconsolable. He refused to accept that a hemorrhage had cut off the blood supply to his wife’s brain. He had instantaneously lost both his life partner and his mind-boggling, new hope of becoming a father. He alone, among the bridge players, could remain in their retirement village.

A few nights after Hilary’s funeral, Jason hung himself from the clubhouse ceiling. No one had known that he had told Hilary, at the osprey and coyote exhibits, during the club’s private zoo tours, that like those creatures, he and Hilary were mated for life.

Despite Jason’s failure to understand the significance of Lionel’s second chance at happiness, Lionel paid attention to both Jason’s death and Hilary’s demise. Hence, Lionel insisted that he and Carrie skip all forthcoming Thursday night games. Hastily, he relocated himself and Carrie to their New York City pied-à-terre. There, a salaried nanny helped them decorate, supervise contractors, and in other respects prepare for their future.

The club’s spare pair, Suzanne and Rudy, had already permanently replaced Joanne and Zaccheus. Without Hilary and Jason, and Lionel and Carrie, the club no longer had full tables. The members were reduced to playing rubber bridge.

The problem was that half of the club, specifically, the temperamental, bun-filled ovens, loved only duplicate. Consequently, Princess and Seymour moved out a month ahead of schedule.

All of a sudden only enough couples remained in Golden Days Retirement Community’s Thursday Bridge and Cheddar Cheese on Crackers Club to set up a lone table of male players and a lone table of female players, plus a spare pair who could be put to use heckling. That plan barely lasted four days.

In no time at all, the bridge players were forced to choose between returning to rubber bridge or to playing mixed duplicate since both Gertrude and Linda had to be hospitalized. Gertrude’s uterus was hosting a private dance party and Linda had preeclampsia.

Allen and Antonio carpooled to the hospital. Allen brought thermoses of coffee. Antonio brought change for the meters.

Over tens and aces, Suzanne sobbed that she missed Gertrude’s diatribes about amanuenses and savants. She shed further tears over how wonderful it was that Rudy had married her and about how horrible it was that puppy mills existed.

Stuffing handfuls of Swiss and Gouda cubes into her mouth, Maribelle nodded in agreement about her own relationship to her husband, Thomas, and lamented her lack of access to Linda and that woman’s social advocacy. Maribelle whispered aloud that all animal shelters should be no kill, but Suzanne heard her and began blubbing anew.

Maribelle shrugged and then reminded Amal that when Linda was carried to the ambulance, Linda had shouted out apologies and had admitted that Maribelle had been right that the world, into which their children would be born, was dreadful. Linda’s last words, screeched as the attendants were shutting the ambulance’s doors, were that the bridge players being forced to leave the retirement community was bad, but bridge players being ridiculed for being “mothers of advanced years” was worse.

Suzanne kept crying. Amal shrugged and then piled her plate with water biscuits and oyster crackers.

A few weeks later, Suzanne was shipped to a New York City level six hospital. Very belatedly, her obstetrician had discovered that she was having twins and that they were trying to prematurely birth themselves.

Just Amal and Maribelle carried their pregnancies to term in the retirement village. Although they were under increasing pressure to move, their nesting instincts prevailed over their received legal documents.

Most days, those two visited each other to compare notes on the anchovy and apricot omelets they had taken to eating. Occasionally, they sniggered over new ways to increase the elasticity of an article of clothing’s waistline.

Thomas, Maribelle’s husband, answered the phone when Vili, Amal’s spouse called. His and Amal’s midwife had delivered their boy. Because of an accident on the New Jersey Turnpike, Amal, who was thirty-eight weeks and three days pregnant, never made it to the hospital. Fortunately, her labor coach, who was also a certified midwife and a wise woman versed in several cultures’ worth of birthing lore, had been in the car with them.

Maribelle stewed through her thirty-ninth and then fortieth weeks of pregnancy. At forty-one weeks, her doctors threatened to call Child Services if she refused to be induced. Child Services was never contacted, though because Thomas and Maribelle, too, birthed outside of the hospital.

A middle of the night bathroom break was quickly understood to be second stage labor. Thomas, tutored over the phone by local paramedics, caught his and Maribelle’s daughter.

The members of Golden Days Retirement Community’s Thursday Bridge and Cheddar Cheese on Crackers Club never learned why they, individually, and collectively, were gifted with late life pregnancy. All that they ascertained was: gated residences take unkindly toward young, squawky residents, the death of a spouse is tragic, but suicide is worse, pregnancy is hard on women, especially ones in their twilight years, duplicate bridge is more fun than rubber bridge, and people are never too old to love their babies.

———————-

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.