Matthew Levine

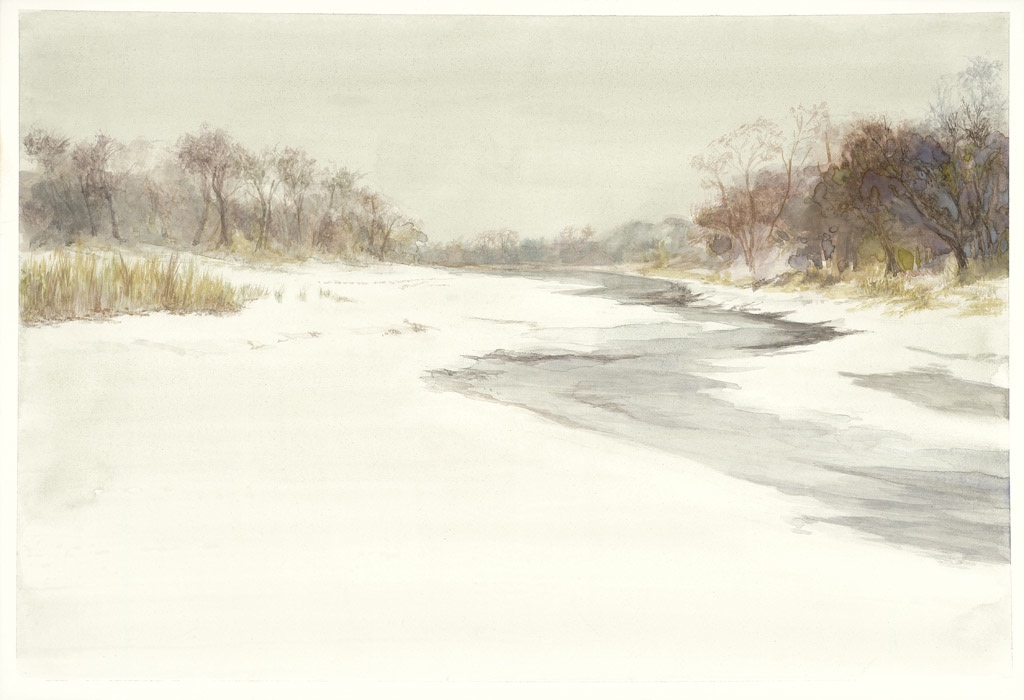

First Snow, Gray’s Creek

Watercolor

Inspiration piece

The Ground

By Robert Haydon Jones

Response

Jimmy O’Hara might never have seen the book, “Wild Life of Coastal New England” that his mother had given him on his fortieth birthday if he hadn’t promised his wife, Anne, that he would clean out the jumbled book cases in his home office.

The book was at the bottom of a vertical pile in a horizontal space. He had never seen it before. Not that he could remember. He had enjoyed going through his old, stowed, books. As it turned out, he wasn’t cleaning anything out. He was rearranging the piles. What was he supposed to do – throw out The Complete Collected Rumi and the Bill James Master Abstract of Baseball?

But the Wild Life book was a joker. Jimmy had no idea where it had come from. So he opened it and instantly saw his mother’s handwriting on the flyleaf. “To my wild child on his fortieth birthday. Jimmy — there’s still time to become a naturalist when you grow up! Love, Mother.”

He had been on a run on his fortieth birthday – that’s why he couldn’t remember getting the book. Actually, his 41st year toward heaven had been a series of runs. Jimmy had more or less disappeared for that year and the two straddling it. He was doing speedballs and he couldn’t stop — even when he really, really wanted to stop.

Now her wild, first-born, child was many, many, years sober. His mother had been dead for a long time when he opened up the book that didn’t belong in his bookcase and saw the message she had inscribed to him back then.

Just the first glimpse of her handwriting had immediately flashed her to him. She was a strawberry blonde beauty. In 1944, Jimmy had seen her literally stop traffic as hand-in-hand they disembarked from the top deck of a Fifth Avenue bus.

She was petite and fine-boned – yet she radiated feral strength and power. If she had been a man, she could have been a boxer or a runner or a soldier. But she was a woman in the early 1940’s – so she was a wife and a mother. Sadly, it took just one drink to undo all she was – and even now, decades after the fact, Jimmy and his brothers and sisters often flinched when someone suddenly raised a hand to, say, brush back a lock of hair.

“Still time to become a naturalist.” Jimmy still lived in the seaside town in Connecticut where he had been raised.

As a boy, he had roamed the hay fields and tended cattle on the hilly pastures. The biggest hill had been the site of a battle during the Revolutionary War. The hill ran down to the sea. In the winter, he slid down the big hill again and again on a 4-man toboggan. On one of these runs when he was 12, he embraced the comely wife of a neighbor. It was a moment he would never forget.

He played baseball in a meadow close to the sea. In late July, they had to stop. Then the farmer would come and make the first cut. Three days later the field was level and they had two hay bales to use as a backstop.

He shucked clams and oysters for Captain Fergus, the mean old wholesaler, through ten thousand nasty little cuts — until finally he could do it fast like it was nothing.

He played pick-up tackle football on an empty sunken lot across the street from the sea. Usually the ground was somewhat moist and yielding. The fact was the ground was an essential element of the game they played. After a play, you would lie there for an extra beat. This ground by the sea had a throb to it. It felt good.

Most of the houses in the beach section where he lived had been built in the 1890’s as summer homes. The developer had acquired a dozen large apple orchards – and had the good sense to spare as many trees as possible.

The apple trees were always the crux of the atmosphere of this place. Dead and gone in winter in gnarly rigor mortis. Implausibly budding again even with snow still on the ground in the early spring. Then the sudden cascade of blossoms – so for months and months — the moment he stepped beyond the arc of the sea breeze, he was enveloped in a scent that reeked of romance and eternal love.

There were thousands and thousands of apples on the bough. He picked them for money on the days of long light in autumn after school and on the weekends that dimmed down to night till all of a sudden you couldn’t see.

When he sank down into sleep it was billowy with the hard outdoor labor and he dreamed Frost’s apple dreams and slumbered deep, deep down the apple rumble into the woodchuck’s chamber that is reserved exclusively for pickers who have been rubbed for hours and hours by apples and stems and bramble — whose soles are certified by rungs forever embedded — like tattoos in invisible ink.

He knew the trees well. There was a stand of succulent Golden Delicious that the owner picked himself. Jimmy stole from it as much as he could. He brought these apples home. His mother said they were the best. She once wondered aloud if they tasted extra good because they were stolen. Jimmy hadn’t known she knew.

There were scores of apple trees no one picked. They stood on property whose owners didn’t want anyone on their ground. They rejected all offers for the fruit.

In time, almost all of these apples fell to the ground and moldered. Then these were the fruit at the center of the atmosphere. Until the first hard frost, it smelled as if there was a gigantic cider press near by.

“Still time to become a naturalist.” Part of the shoreline flowed into a tidal swamp. There was a small clump of firm hummocky ground bordering the swamp on the roadside. Several weathered headstones were scattered about the half-acre. In the early 18th century, a band of colonists from Ennis, Ireland had settled here. The swamp was close — the ground was cheap. Cholera killed all but a few. The survivors went back to Ireland. One of the survivors had been his mother’s great grandfather.

There had been a skirmish here in the Revolutionary War. One of the headstones was supposedly for an English soldier – but no one knew which stone it was. Jimmy’s little brother, Lou, found an old sword and Miss Jenkins, the librarian, took it up to Yale. She said she thought it had belonged to an English Officer. Jimmy didn’t remember if they ever heard back from Yale.

The swamp cemetery became a traditional meeting place for the neighborhood children. Jimmy and his friends played Cowboys & Indians here – and War against the Nazis and Japs. One day in May, Jimmy and five of his friends took off all their clothes and compared penises. It was exciting and wrong. They did it again two more times and stopped.

When Jimmy was 12, he and his friends dug into the side of one of the hummocky hills and hollowed out a space big enough for five or six of them. They called it a fort. They stocked it with flashlights and made a floor out of Army surplus shelter halves. The fort was pretty much invisible even when you were close to it because it was dug into the side of the hill.

Some times Jimmy would go to the fort by himself and read a book and look out at the swamp. There was a lot going on depending on the time and tide. There were muskrats and swans and gulls and cranes and herons and hawks. In the late summer, blue fish broke water after clouds of frantic minnows.

There was a big blue heron that fished right close to Jimmy every time he was there. When the heron flew in, it stirred Jimmy every time. When the heron flew away, Jimmy was surprised every time by the power of the lift off and the grace of the curling ascent.

When Jimmy was 14, he and Brenda went to the fort all summer long. Usually they had it to themselves. It was like having a house. They talked a lot. They listened to a portable radio. They necked a real lot.

In August, right before Labor Day, they tried to do it. They tried and tried but Jimmy couldn’t break through. The day after Labor Day, Jimmy went away to Prep School and in October, Brenda moved to California. He missed her but he didn’t know then that he wouldn’t see her again. Jimmy never went back to the fort. He figured other younger kids would be using it.

“Still time to become a naturalist.” It had been 61 years since he had been in the fort. He passed the swamp and the cemetery often on his way to the beach. The swamp was unchanged. The little cemetery had been tidied. There was a narrow asphalt path through it and a marker had been erected commemorating the failed settlement and the family names of the interred. He had scanned the marker from the road. His mother’s family name was there all right. There was no mention of the dead English soldier.

The pastures and fields were gone. The big hill was now studded with big houses. There was no place for cattle and no room for toboggans. There was no place to play pick-up football or baseball. All the apple trees were gone. He was well aware that the town had been filled in, but he was surprised and disturbed all the apple trees were gone.

Captain Fergus’s shack on the cove was gone. There was a “Scenic View” parking area for ten cars. The water’s edge was strewn with mounds of shells. Jimmy wondered how many were his. Jimmy – the midden man.

He had lived here all this time his town had filled in. Did that make him complicit? The fact was that from the time he had left the fort with Brenda, he had never been back to the ground. Not here. He’d been on the ground plenty in the Marines – and then camping afterward with the wife who liked to camp. But then she was gone and he had never again lain on the ground.

“Still time to become a naturalist.” It was just a ten-minute drive back to the swamp. Jimmy parked on a side street. He walked across the road and then along the path through the cemetery. He clambered down the side of a hummock looking for the fort.

He was surprised he found it so easily. He parted some scrub bushes and there was the opening. Narrowed, but he quickly enlarged it with his hands. He could see the remnant of the shelter halve floor – and a rusty flashlight. It had been a long time.

He sat down by the opening and looked out at the swamp. Just then, a blue heron that had been feeding in the narrow channel thirty feet out, suddenly rose and spiraled away.

——————————————————

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.

9 Comments

This doesn’t just evoke a mood. It evokes reality and a world this reader grew up in and loved. Rob Jones just keeps getting better.

This is what Amy Lowell would called “polyphonic prose,” or a prose poem, thanks to the internal rhythms and half-rhymes. Jones knows how to intoxicate while weaving tales.

Apples aroma mouldering Adam and Eve and apple trouble.Forts penises and mini soldiers all gone now . Nostalgia galore for a past that is only gone forever. .Well done Mr Jones there is a tear lurking here

Rich, sensual prose. Poetic. Things change. But our heart, soul, and body remembers. Moving story. And the painting set the mood so well.

Both story and painting are dripping with feeling. Enjoyed them both very much.

Best line “it was exciting and wrong. They did it two more times, then stopped”. Ha! I laughed out loud!

Some really great descriptions in this one. The ground by the sea has a throb to it, as does the story.

Evocative and wonderful; I’ve got a lot going on in my life but this story made me forget it all. Sense memory prose is difficult to pull off without overt sentimentality- but RHJ’ details keep surprising me and I felt clear memories and a full heart.

Matthew’s painting is beautiful

In reading I felt aptly and comfortably near to Gray’s Creek portrayed in the watercolor. The author beautifully conveys what we “carry” with us as we’ve scouted, hunted, played, invented, loved and lived.

A wonderful ride thru childhood memories, energized beautifully by Mr. Jone’s prose. I somehow shared his nostalgia throughout the read.