Cathy Stevens Pratt

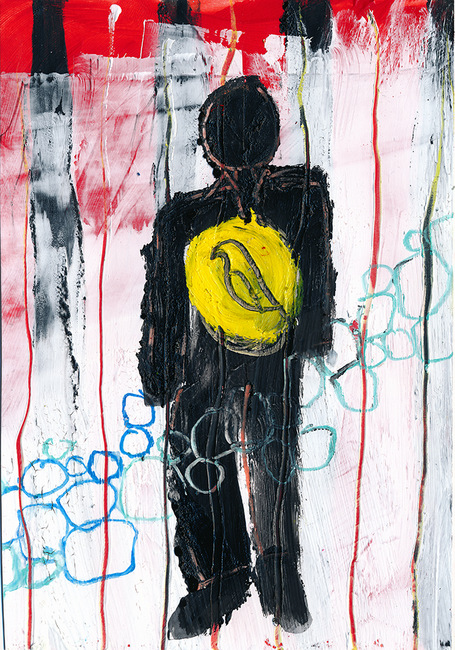

Response

Herr Mittemeister

By KJ Hannah Greenberg

Inspiration piece

A bird whistles. Herr Herman Mittemeister hums an accompaniment. His voice shines.

Likewise, his hair and nails are neatly trimmed. His uniform is free of wrinkles. His face, however, is lined and shadowed. It is his visage, rather than his singing, which provides a counterpoint to the avian’s melody.

Mittemeister looks through his cell’s window. He regards the nightingale with which he is trying to harmonize. He then looks past the tree, on which the bird perches, to the Danube. His prison sits on Handöfel Island.

Mittemeister can see only one shore. There, the town of Tolksburg rises. In that town’s marketplace, merchants are settings up stalls.

Among the sellers are the farmers, whose land fringe the valley containing the river. Similarly, there are tutors, whose homes dot the hills around the valley. As well, creative persons self-referenced as “craftsmen” vend vessels, paintings, clothing, and more. Additionally, peddlers ring bells and beat pots to draw attention to matches, to toys, to live animals, and to knives.

Four years earlier, when Mittemeister, Eric Kluger, and Carl Grosser were enrolled in university, they had dared each other to skip a day of class. Rather than listen to their professors’ lectures, the threesome had walked among women bickering over apples and mackerels and among butchers busy with large, broad blades.

The streets had been crowded and the air, too, had been chockablock with the hoots of the wind, the chants of sellers, and the music of birds (many of those sky fish had been the same species as the one with whom Mittemeister made music from his cell.) Regardless, at the time, the noise had meant that Mittemeister had barely been able to hear his friends’ “wisdom.”

The boys had settled in a beer garden and had been comparing the worth of various brews. Eric preferred Schwartzbier, but Carl was partial to Doppelbock.

“We’re both right. Let’s, dear sirs, drink to beer. What is better than a beer?”

“A friend. What is better than a friend?”

“Be realistic.”

“Entirely. What is better than a friend?”

“The three of us, our coterie!”

“How cliché.”

“Yup.”

“Heads, I win, and you buy. Tails, you lose, and you buy.”

“Huh? Let me see that coin.”

“No. No. Be a gentleman, Sir. You buy.”

“It’s too expensive.”

The two had leaned toward Herman Mittemeister for his opinion on who should pay. Their conversation was abruptly interrupted.

An elder, in green work fatigues, hobbled past their table. He was huffing and puffing while making his way to the seating area where men in expensive-looking woolen coats had gathered. That elder bowed slightly upon approaching the well-heeled magistrates.

Eric shadowed him.

The beggar extended a cupped hand. The men of power ignore his gesture and spoke amongst themselves.

“Beautiful morning.”

“Remarkable, Sir.”

The beggar interrupted, “sirs?”

The men continued to ignore him.

“I adore market mornings. It’s beneficial to witness productivity. Erroneously, I had believed that after the bridge was completed that the townsmen would be badgering us for more projects, but, as you can see, they seem preoccupied with chickens, pies, flowers, and knitted hats.”

“Remarkable.”

The beggar interrupted, “sirs?”

“Word is that some of the workers were injured…”

“…and dared, subsequently, to apply for pensions!”

“Remarkable.”

The beggar again interrupted, “sirs?”

“They received nothing, right, Heinrich?”

Herr Schultz nodded.

The beggar once more interrupted, “sirs?”

“‘Nothing,’ I said.” The magistrate picked up a stone and hurled it at the beggar.

His companions, too, pelted the beggar.

“Remarkable.”

Eric shouted at the men, “stop!”

From a distance, Carl taunted, “yeah, stop, stop, stop, good sirs.”

The magistrates tossed all manner of uncharitable phrases at the limping beggar.

For his part, the old one merely pointed to the bridge.

One of the rich ones shouted further epitaphs at him.

The old man crept closer to the wealthy ones.

They threw more stones.

“A disgrace!” called out Eric. “He’s a sage, a man to be venerated, not disparaged.”

“You’re blind,” retorted Carl, who had walked nearer to the commotion. “He’s a day laborer who was injured while working on the bridge. He wants alms. My father says such men are parasites.”

“You, my friend, are a privileged idiot,” responded Eric.

“You waste your days twiddling,” said Carl.

“I say not.”

“I say so.” He pushed Eric.

Carl and Eric began to fight. Mittemeister tried to separate them but was thrown against a merchant’s stall. The magistrates stopped pelting the beggar and regarded the boys.

Eric and Carl had rushed deeper into the market, where they “acquired” lethal tools from some of the fish mongers (those dealers, who were bored with scaling and gutting, welcomed that entertainment.)

The two youths upheld no gentlemen’s code of conduct. Neither blocked each other’s attacks, preferring, instead, to reduce the distance between them with each parry.

On one level, the two were well-plumaged birds. Carl wore an orange shirt topped with a matching vest emblazoned in gold and green. Eric’s blouse was stippled gray and his vest’s ornaments were beige. On another level, they were stupid boys.

“Our friendship club,” screamed Eric as Carl fatally wounded him and then stepped away from Eric’s body.

Mittemeister, who at last, too, had left the beer garden and had run to the scene of the fight, pulled the knife from Eric’s body. He stabbed the beggar. “For Eric, Sir. Good morning.” He then threw himself over the beggar and sobbed.

Tolksburg grew instantly quiet. No nightingales sang. No hausfraus fought over cakes. No merchants touted socks or knitting needles.

“And you are little better than Eric,” said Carl before he disappeared into the crowd.

“I just wanted peace among friends,” was all that Herman answered before he was dragged away.

****

To the right of his cell’s window is a calendar. A date is circled on it. To the left are a bed and a three-legged stool. On the bed rest a charcoal stick and some charcoal drawings.

After the murders, Herman had pleaded innocence, claiming that his had been a righteous intent. His words, however, had been entirely ineffective; while he was offering up arguments for his freedom, his lawyers had spoken amongst themselves about racehorses and brothels. Thereafter, unceremoniously, he had been deposited in jail.

Mittemeister again regards the wall calendar. It’s the fifteenth of the month, the day when Carl ordinarily visits. Herman never specifically questioned why Carl calls on him every two fortnights. Long ago, he had stopped questioning Carl altogether.

Be that as it may, the guards like Carl’s visits. He brings them chocolates and whiskey and promises to compliment them to his father. Accordingly, they let him access Herman’s cell and the prison’s music room. Every month, Carl gives Herman a recital.

Sometimes, though, Carl fails to appear. Those times, Herman crumbles his drawings and talks to himself. “Good morning sir. Good morning. Another Handöfel morning. Ah, morning. One morning. Two mornings. Three, ten, then a year, two years. Four years of mornings. I’ll be as old as that beggar, soon.”

Mittemeister looks at his pile of drawings and crumples each one. “Mornings come. Mornings go. I remain. Morning after morning, I remain all because of a singular morning.”

He shakes his head and searches, beyond his window, for the nightingale. “Hello sir. Good morning. You will, as well, I suspect, have a good evening. Evenings as well as mornings. Imagine! You sit here or you sit there. You decide. You choose. Yes, good sir, good mornings!”

Someone knocks on Mittemeister’s door. The guards never knock. A key is turned. The guards never unfasten the door.

A young man of similar age to Herman Mittemeister enters. He has a ruddy complexion. He smiles. Before speaking to Herman, Carl looks at the calendar. Next, he embraces Mittemeister.

“So, what do the folk of Tolkburg say about me this week?”

“It is wonderful to see you so healthy, Herman.”

“Almost as healthy as you.”

“You will be. Soon. You’re leaving.”

“Good morning to you, too, Sir.” Herman untangles himself from his friend and looks out of his window. “I’ve not yet sprouted wings.”

“Wrong.” Grosser hands Mittemeister a large envelope, which Mittemeister slowly opens. Inside is a notice. In addition to the notice, the envelope contains many drawings, all of which resemble the ones he had just destroyed.

“The townsmen have forgotten, Blessed day!”

“Not the officials?”

“No.”

“Really forgiven?”

“No, but forgotten. That’s nearly the same. Not all of life requires patience.”

“My sentence requires.” Herman turns once more toward the window. With his back toward Carl, he asks, “Is Frauke well?”

“Her father, Herr Wexler, remains impartial, but Frauke pushed him. Lucky bird, you, that Wexler heads the council.”

“So, we’ll have no wormwood piano or discolored music sheets this morning? No Bach or Beethoven?”

“This offer is grander, more than generous, indeed a miracle!”

“No! No! No! Parole to Zwischen Street would still be an imprisonment. I’d still live in a locked room. I’ll still suffer more mornings, mornings, mornings.” Herman again looks for the bird, but it is no longer visible.

“Isocrates taught that learning is a combination of practice, ability and …”

“The bird is gone. Gone! Why ought I to trade one musty hole for another? I was here when you last visited as well as the time before that. I will be here the next time and the next.

“Mornings. Mornings. Do you remember the street market? The beer? The patrons? The autumn leaves? The people? There were so many people and so many goings-on, yet it was just one morning.

“Eric had promised that skipping school would be fun. I like fun. You like fun. It was just supposed to be one morning.

“Do you know that every day, after sunrise, a bird sings to me? When the river’s currents increase, it flies away, only to return and then to flee again.

“I can neither fly nor flee. I can barely sing. My mornings begin where my nightmares’ end. Every morning is the same morning.”

“We live in the present.”

“Not me. I dream, always, of that morning in the market and then I dream that dream all over again. I go from sleep to morning to sleep to morning.” Herman thrusts the envelope containing the drawings and the letter at Carl.

“It was a long ago morning.”

“Will you listen, Sir?”

“Leave with me, Herman.”

“Why? No one believed me that morning. Forgotten is not forgiven”

“I believed you.”

“But I have no belief in you. You come and go despite your similar deed.” Herman shakes his head.

Carl pats Herman’s shoulder and then exits. He locks the cell door.

Mittemeister rattles the door and then shouts through its food slot, “Sir, will you never listen? Tummler is to be hated, Hoch to be adored, while Schultz and Wexler remain idiots. Mornings! Mornings! My life is nightmares of that wretched morning.”

Much later, Herman, who is once more looking out of his window, whispers “Frauke.”

****

Sometime later, guards escort Mittemeister to a nondescript building. A nearby sign reads “Zwischen Street.” A young woman with impeccable posture and steely eyes answers the door. Her father, Herr Wexler, hurries to join her.

Wexler signs the guards’ ledger. He motions Mittemeister inside.

Once the door is closed, the woman hugs the Herman, and is about to kiss his cheek when Herr Wexler coughs. The woman backs away and bows slightly to her father. Softly, she says, “welcome home, Herman.”

****

Inside a chapel, a minister, several armed guards, Herr Wexler, his daughter, Frauke, plus Carl Grosser and Herman Mittemeister crowd around a small desk. Frauke Wexler and Herman sign a paper.

Carl sticks a flower in Mittemeister’s lapel.

Frauke, who is dressed in finery, beams.

****

Mittemeister looks out of the lone window in his small chamber. His room is furnished with a bed, a three-legged stool, a table, and a sink. He shakes his head at what’s missing from his view and then hums the counterpoint to a nightingale’s song. He is not answered.

Frauke, pregnant, regards the charcoal sketches Herman left on their bed. “You are enraptured with the music of hatchlings, but not with me. I ought never to have encouraged your sky, your clouds, your rain, or your nightingales.

“Other men care for livelihood, for women, for drink. Not you. You’re nature’s lover. I wish you loved me, not your rivers and feathers.

“At least, I celebrate your talent. At least, I appreciate that you’re special.”

****

In the Tolksburg market, a merchant calls out, “Over here. Yes, you. Hurry while you can still buy a Mittemeister. Note the fine lines, the round shapes. No other artist equally captures the tiniest aspects of aerial beasts. He’s our Grosse Künstler!”

Another merchant chants louder, “No! No! Shop by me. I, too, have Mittemeister’s work. Look at the Danu pouring under the bridge. Regard the stone’s shadow and the water’s depth. You could drown just by looking. Good prices are to be had here.”

Yet one more merchant attempts to outshout his peers, “I’ve the best! Mittemeister’s interpretations of Handöfel are here. Did you ever see such contrast between what is and what might be? Did you ever witness such brilliance given over in limited strokes? If you want something cheery, I’ll sell you cherubs. Today, though, you must look at the curls on these winged messengers. Mittemeister’s a mad genius. Some say that his birds resemble Herr Wexler!”

The second merchant screeches, “don’t leave without purchasing. You can’t visit the Grosse Künstler, but you can buy from me. These works boast fine lines. Look at the careful shading.”

The first merchant counters, “Buy from me. I’m friends with his friend’s friends’ friend. I get the newest and cleverest of his art. Look at this one; a bird and the river! For years, he’s only rendered decrepit buildings, diseased citizens, and deal fowl. Today, I have a couple laughing and a river flowing.”

The third merchant trumps him, “no, look at this one; I call it “Morning Murder.”

****

Mittemeister’s work hangs in his prosecutors’ council chambers and in their homes. Yet, the corners of his home remain unadorned. In fact, he frequently feeds his fireplace many of the images that he could otherwise have sold.

Elsewhere, things appear proper. There are stacks of coins in his proper kitchen. Three young children play tag in his proper office. His wife greets visitors in their proper parlor.

Toward the end of each day, the family’s nanny bathes the children in a proper bathroom and tucks them into bed in a proper nursery. She then retires to a proper servants’ wing.

Frauke and Herman talk together softly in their proper salon.

Herman sighs, “so much money.”

“So many mouths.”

“For charcoal, Frauke. Each is a morning’s work, at most.”

“For freedom.” She sighs, remembering spans when he had put his charcoal away and had laid his head over her heart. He has not touched her for a very long time.

Herman sighs, “yes, such elaborate freedom. There are guards at the front door and at the back. They are not stationed to keep robbers out.”

Frauke gets up, wipes her hands on her apron and sighs. “Herman, make me a picture. A bird, maybe one perched on a branch above the river.”

“Maybe not.” He begins to cry.

Frauke kneels beside him and rests her head on his lap. She, too, cries. “I missed you so much when you were imprisoned.” Carl offered to marry me. My father offered to send me away to another country. I would not abide either.”

“Maybe, I could draw one more bird. Maybe, it could be perched.”

“The children would love it.”

“The children…”

“…are growing. Greta needs a ‘big girl’ apron. Stephen should be wearing long pants at his age. Just sketch a few small ones.” Tiny puffs of air move out of her nostrils.

“One. No more. A bird. A morning’s work, at most.”

****

In the middle of the night, while his servants, his spouse, his offspring, and their nanny are asleep, Herman paces. Every few minutes, he looks out of his workspace’s window. He sees the moon. He sees the river.

A few hours into this pattern, an apparition resembling the dead beggar appears. The ghost waves at Mittemeister, “come.”

Mittemeister shakes his head. “I’m a would-be artist, nothing more.”

The ghost reiterates, “come. Reach the bridge. Touch the keystone.”

Amazingly, the guards at the backdoor are missing. Mittemeister walks out into the night.

****

Frauke and the children are dressed in black. Herren Wexler, Tummler, Hoch, and Schultz bow their heads over hymnals. Carl Grosser smiles at Frauke and then clears his throat before reading. A dirge plays.

Grosser whispers to the magistrates, “too much, sirs, too much.”

Herr Wexler answers, “it was a mistake. Probably Mittemeister thought the gallery owner was a robber. Odd, though, that the guards were absent. They’ve been fired.”

“Why would he try to steal his own work? He hated it. He destroyed far more than he sold.”

Herr Hoch quietly added, “remarkable. First Handöfel, now this.”

“Will the merchant be charged?”

“Yes. The proceeds will provide for the family. The council can ill-afford the upkeep of…”

Carl interjects, “…orphans and a widow? I encourage you to review the law.”

All mourners exit except for Schultz. Herr Schultz looks at a paper, which slipped from his hymnal. It shows a bird taking flight. He tucks the sketch into his jacket.

________________________________

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.