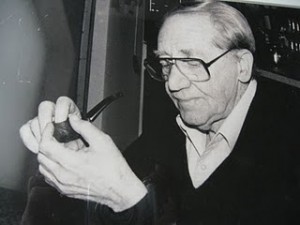

MM Panas

22

Mixed media on paper

Inspiration piece

John Panas

Photograph of 2010 winter storm

Absent

By Mary L. Tabor

Response

The camera was invented in 1839 by arguably Fox Talbot—some say it was Louis Daguerre, but whatever the controversy about its invention, its mark on our lives is indelible. The photograph defines for better or for worse: Think of family, think of presidents and kings, think of wars and holocausts, of earthquakes and broken houses, think of tidal waves and flooded land, think of volcanoes and moving bodies frozen in ash, think of slow-moving glaciers and grand canyons, or simply think of blizzards and great pines struck down by flakes of snow.

No photo of my father when he was a child exists. One family photo of his parents and his six brothers and sisters stands as proof of who they were. The photo belonged to Cecelia, my father’s niece who died this fall, whose life became entwined with his well after this photo was taken.

I ask, Can absence be defined?

The only photos that mark my father’s existence begin with his marriage to my mother. He came to her with one shopping bag with everything he owned, that included one small framed photo of his mother Hannah that sits now on one of my book-lined shelves in the condo where I write.

Cecelia’s mother Rose stands tallest in the family picture but she succumbed at thirty to tuberculosis when Cecelia was seven and my father, thirteen. And so their lives joined. She and Rose lived with my grandmother while Rose died and when she did, Nathan, Cecelia’s father said he couldn’t take her. Gerson and Cecelia ate fried matzo and gefilte fish, bought, when they could, corned beef sandwiches and split-grilled kosher hot dogs on Lombard Street. They cleared the china from the table. They translated the English Hannah, who spoke only Russian and Yiddish, needed for the blocks she’d walk where she felt safe. They became brother and sister.

My father never forgot the day that Cecelia was wrenched from his mother’s arms. Her father had remarried and came when she was just thirteen to take her away. My father never forgot her screams as she was shoved into the car to live with a woman she’d never met and would never find a way to love. They shared this memory that even her children don’t know—as if it didn’t happen.

No other photo of my grandfather exists.

Harry, a tailor in Russia, and Hannah escaped a pogrom through a sewer with Rose who lived because, when she cried and the guide said she must die, she suckled at Hannah’s breast. Harry couldn’t find work as a tailor in Baltimore. He died on the street where my father found him in the gutter he was cleaning, struck down by a heart attack, lying with his broom.

Gerson barely graduated high school. His geometry teacher was a drunk and Gerson wrote that on the board and got expelled. The truth is crooked and should not be chalked.

He couldn’t afford the photo or the yearbook from Eastern High School in East Baltimore where he did get that diploma, but didn’t walk across the stage: No one to come see him.

He played pool in a pool hall where he met a lab technician whose low-level job at Hopkins gave him time and money for pool and opera and books, who could see Gerson’s mind and where the gambling would land him. He lent him Return of the Native by Thomas Hardy. Gerson read that one and every other Hardy wrote. Gerson read The Forsyte Saga by John Galsworthy. He visited the lab technician’s flat on East Baltimore’s Broadway near the lab and not too far from Milton Avenue, the street and neighborhood Hannah dared not venture from, where she was putting briskets in the oven. He heard the notes of Wagner and Beethoven and Chopin, the voice of Enrico Caruso on a gramophone. Reading was his game now. Opera, his obsession.

He wanted to go to Towson State Teachers College and go back to Eastern High to teach literature, to show the drunk how you really chalk the board. He couldn’t afford the 15 cent trolley fare in 1924. He sold shoes, earned five bucks a week and gave two to his mother.

My father didn’t live to see my first book published.

He gave me my first book: Green Mansions by R.H. Hudson with its heroine the sylph, Rima, who he always said I was. This book that I still own is boxed in a black protective folder that sheds, crumbles in my hand when I remove the treasured gift, the book still perfect, that my father gave me when I was a child. I traveled without passport to the erotic and the primitive, to the wilderness and came back changed.

He took the home movie of me in my Davy Crockett buckskin jacket that I wore walking down the tiny stoop of our Grantley Road row house. He took the shot of me while I twirled and that my lover stilled from my father’s yellowed eight-millimeter film and placed inside a frame to give me when I left my corporate job to write.

He is the missing man in the photo of my erotic life. And here’s the proof: My lover has his wit—the circumstances are extenuating, said my father. My steed at the ready, ma’am, says my white knight with no armour. My lover plays Schubert on a baby grand, listens to Chopin and Greig, owns a woofer that he built for the stereo that resounds. My lover reads Saramago and McEwan and McGuane—and everything I write.

The philosophical chestnut asks, If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it … ?

I ask this question, If my father is absent in the family photo, is he missing?

…

…

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.