MM Panas

Response

Sine Die

By Mary L. Tabor

Inspiration piece

Excerpt from The Woman Who Never Cooked, Mid-List Press, 2006, First Series Award; previously published Hayden’s Ferry Review, winner Prentice Hall Fiction Prize; Grand Prize Winner Santa Fe Writer’s Project

I see the two women at the bar, yellow silk, split skirts, dark hair, beautiful long thin legs.

The two women were at the bar, thinking they were in Hong Kong, pretending. (Much of what they do is pretending—it is how they get on with one another.) Today they pretended that they were Asian, that their hair was long and straight, that they could smoke without harm, that they could drink and stay in control but still get high, that their skin was the beautiful mellow beige of Asian women, that they could lie in the sun without burning. They talked and laughed. They wore their hair pulled back against their heads, made smooth with gel so they had the look of straight hair. They went shopping and bought yellow silk blouses and skirts, went to a seamstress who cut the slits in their skirts, who tightened the silk against their hips.

The only way to tell them apart is the younger sister’s small bones, tiny points, exposed; the older’s small round stomach. They bought high-heeled shoes and wore them even though both had inherited their mother’s feet—one with the hammer toe, both with the bone that widened at the ball, that had become a bunion as they grew older. One sister’s bunion was worse than the other’s. The bunions, hidden in the narrow vamps of their shoes, hurt. They did not care. They were pretending and they were good at it.

It had taken them a long time to learn. It began when they were children, when they pretended they could fly by riding on each other’s feet, when they pretended they were fine cooks like their mother, cooked mushrooms on toast and created a delightful meal for themselves without their mother’s help, when their parents were not home, when the older sister was babysitting the younger. It was when they were children—like other children—that the pretending became an integral part of their play. But unlike other children, the pretending became so essential to their relationship they could not, would not, outgrow it because, while they were children, one of them got sick. They didn’t talk about the sickness; they pretended, the way their parents pretended, that it did not exist, but the sickness was the source of all their pretending now, the unspoken source.

The two sisters left the bar and went down Baltimore street, the street where the strippers took off their clothes inside the bars. They didn’t go into any of these bars but they liked to walk down the street. So they walked, watched the eyes of the men on them, knowing this was dangerous. But the older sister was strong, a powerful, sick, fearless woman who told the younger sister not to be afraid. She said, “Pretend you belong, that you own the street. Anyone can go anywhere if she acts like she owns the place.”

1

This way of walking, of turning a street corner, of entering a room, is something you can learn by pretending. It’s the key to everything. That’s why we do it when we’re little—so we can learn.

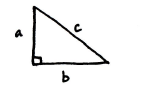

I am not sure when I am pretending and when I am not. I had a sister, three years older than I, who died. I have trouble remembering her. To help with this I think of remembering and forgetting as two sides of a right triangle. I think of the third side, the hypotenuse, as pretending. It is this third side that helps me accept the not knowing, the intangibility of the truth.

Fig. I

…………sine curve

In Trigonometry, the graph of the equation y = sin x is called the sine curve, an elegant mathematical tool for defining the relationship of the sides of a right triangle. It is an infinite (sine die) pattern of undulating curves with an infinite number of points that plot changes in the triangle, including a point where no triangle exists—a flat line.

Figure II

On the right triangle, let us call the two sisters Sides A and B; A is the older sister; B, the younger; they are bound to one another in a right angle, an essential (sine qua non) element. Their relationship, the unknowns and knowns of each to the other, is defined by the sine curve. The unknowns reveal themselves as knowns, as points on the sine curve by calculating the relationships of A to B to C. Side C is the pretending. I think of the sisters (A and B) interchangeably as remembering and forgetting, for as I’ve said the two are hard to tell apart, the way the sisters looked alike that day on their walk down Baltimore Street.

2

The two women were not whores. They were not wild.

The only thing they had ever done together with abandon was the time they cut their long hair short and had it permed, which made their curly hair curlier—and them, ridiculous. Then, like now, they did not know exactly what they were doing, and their hair bloomed into unexpected Afros when it dried. Since puberty, each had rolled her hair and sat under dryers. Neither knew that she had naturally curly hair because both had straight hair as children. The curls came with puberty when all those rollers became essential to their pretense of appearance. In this sense, the truth about their hair was a secret neither had known—that they discovered with a silly mistake, the permanent solution on their hair. The tameness of the mistake and the resulting discovery contrasted with the seriousness of the pretending that defined their relationship and the current adventure.

For now they both knew there were other secrets. Neither knew what the other had done that could have been wild, that they had not done together. Both sisters, who were married, believed that the other had never had an affair. But on Baltimore Street each sister looked at the other wondering if this were true. Had neither actually had an affair?

The older one, the one who was sick, thought, My sickness is like an affair. It seduces me to live even though I know the doctor will cut off my leg soon (this, my sister doesn’t know). It repels me because I would rather die than live deformed. I am infatuated by my secret. When I am ready to tell, my horror will hold my sister near me. What has my sister kept secret? she wondered. To find out, she lied, “We tell each other everything. I would know if you had done something. I would see it in your face, hear it in your voice.”

The younger knew that was not true because she had had an affair with a married man, a lawyer, many years ago before she was married—and not told. She wondered,

Would I sleep with the lawyer now? Now that I am married?

So she was not as innocent as she pretended. Did her sister know this? She was reminded of when they were both teenagers: The older had made her a costume like the yellow silk outfit she was wearing now. Her sister had called it “the gypsy costume.” Now the younger saw that the gypsy costume really was the outfit of a whore, with the low-cut blouse, the skirt with a slit up the side, on a fourteen-year-old girl. The skin-tight skirt, which the thin little girl wore well, pretending to be older. Her thin body suited the outfit, the scarf her sister put around her forehead, a larger scarf around her shoulders atop the off-the-shoulder blouse. Who was pretending? Was it the little girl? Her seventeen-year-old sister? Both, the woman now realized. They were dreaming the shared secret, desire.

The sisters’ most powerful secret was something each knew but would not, could not express—the power of the older over the younger. Both were aware of it. Neither knew how it would play out.

3

My sister is dead. She died three years after our mother died. My father is sick—but because I am left I am the only one who knows about this. My father doesn’t remember that my mother (his wife) and my sister (his daughter) have died. He has severe memory loss—Parkinson’s Disease. He is sine cure (without cure). The doctors simply say, to clarify, “Senility.” But I think he is mad with grief. I am forty years old, married to a man I love. Like my father, I am not sure what I know. I often pretend—now that my sister and mother have died and now that my father can’t remember those facts—I pretend that another man loves me, a man who has no connection to any of these losses. My husband, who I think no longer desires me, went through it all with me—all I’ve lost. I want to forget, to pretend. Perhaps the other man is real. Perhaps my husband desires me. My father sometimes says, out of the blue it seems—is he trying to remember or forget when he says this?—“The circumstances are extenuating.”

…

…

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and written permission from the author or artist is strictly prohibited.